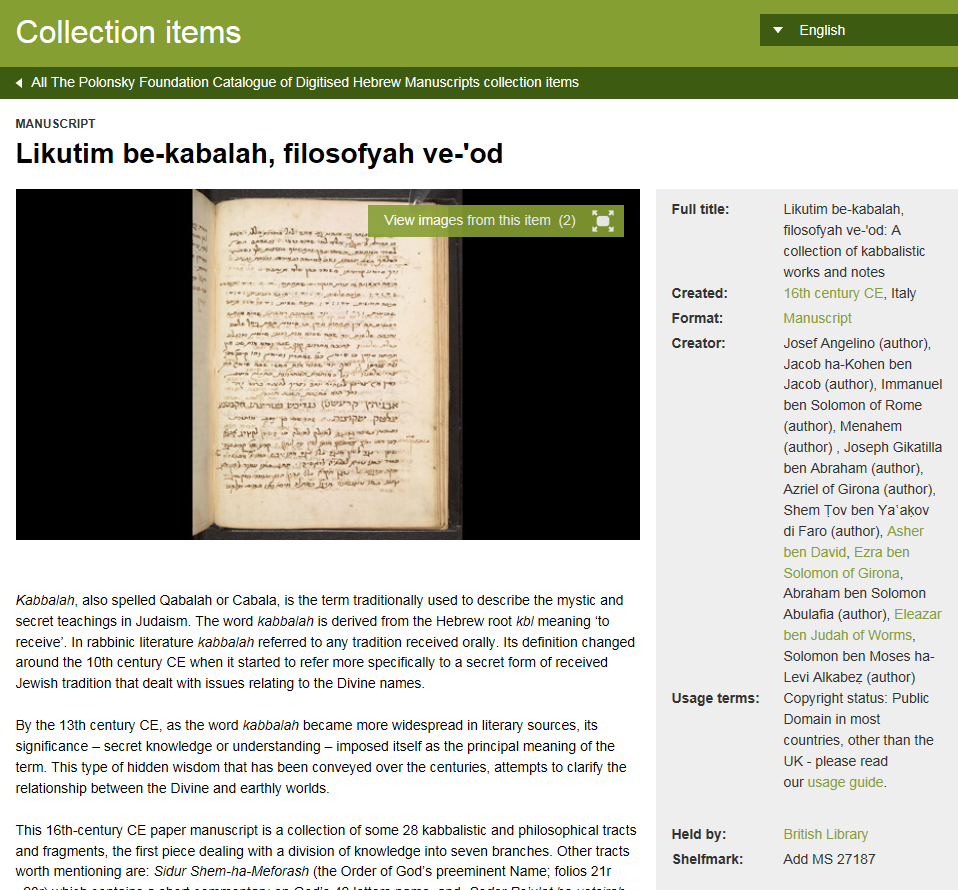

Unlocking the British Library's treasures online

We spoke to Ben White, Head of Intellectual Property at the British Library, about some of the treasures (and challenges) he and the team of curators and project managers have uncovered in their efforts to bring hundreds of thousands of objects onto digital platforms, and show you how to use them.

- Title:

- Key from the collection of Emmanuel Vita Israël

- Institution:

- Rijksmuseum

- Country:

- Netherlands

- Copyright:

- Public Domain

A bit of a copyright challenge

The British Library has developed a policy that guides people through the digitised collections, making it easy for people to see what they can do with its items, and encouraging them to use these objects in their own projects and activities.

No easy feat when you are dealing with, for example, one project alone spanning 60,000 books, or 100,000 sound recordings, over 20 different legacy digital content platforms and a UK copyright system that deems nearly all unpublished manuscripts in the European Economic Area as copyright protected (even if they are manuscripts from the Middle Ages).

One of the library’s latest projects ‘Unlocking our Sound Heritage’ aims to make available online some 100,000 sound recordings (something Ben understates as posing ‘a bit of a copyright challenge’). The recordings range from animal and environmental sounds, to ethnographic field recordings, radio broadcasts, and popular and classical music.

According to Ben, ‘Our policy encourages the use, where possible, of open licences. Where the material is public domain (or, given the uniquely long duration of copyright for manuscripts in the UK, public domain in most other countries), we also attempt to convey this. We encourage access and reuse and make that very clear when we put material on the open web.’

This work requires attention to detail, as the appropriate usage terms need to be assigned to each individual digital object. And given the British Library’s extensive collections, this in some of projects, can add up to quite a lot of work.

Cultural treasures now online to explore and reimagine

However, it is not without a sense of fun.

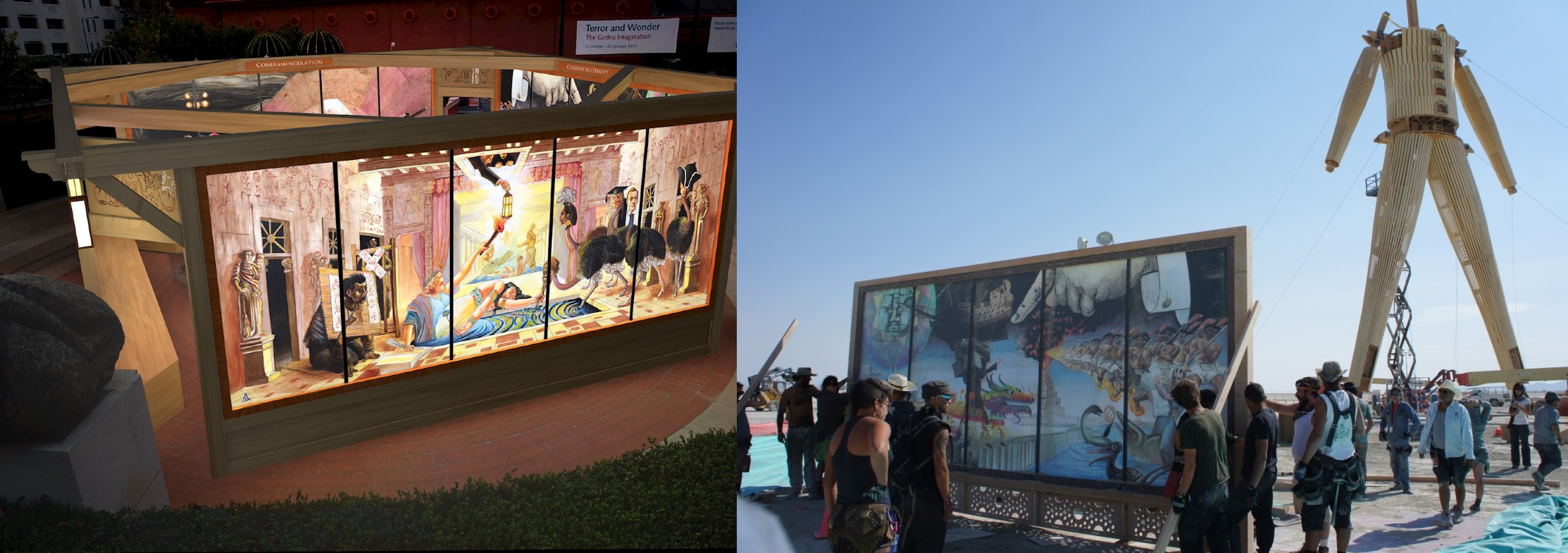

The Library has developed a number of incentives to encourage people to view and reimagine content. This has resulted in digital cultural heritage objects being used as inspiration for fashion collections, card games, large-scale art installations, poetry writing and painting lessons.

One such incentive, a fashion competition, invited UK university students to develop a fashion portfolio taking inspiration from the 1 million images that make up the British Library Flickr Commons Collection. Eight finalists were selected, of which Alanna Hilton of Edinburgh College of Art was awarded the winning selection. Her ‘Unlabelled’ design portfolio used inspiration from the images to showcase a collection that ‘rejected labelling’ and branding and had a target market that was truly inclusive of all ages, sizes, ethnicities and gender.

Further, Victorian Era book illustrations from the Library’s Flickr Collection were also used as inspiration for David Normal's art installation which showed at the Burning Man festival. In line with the festival's ‘Caravansary’, (Caravanserai) theme, the mural installation took shape as a lightbox of imagery and collages.

Sounds and sensitivity

However, these are not the only considerations when you use digital heritage content. In the case of the sound archives, not only will the British Library encourage people to embed and reuse the sounds through the development of innovative IIIF-compliant embeddable technologies, they will also provide sensitivity guidelines that highlight the ethical considerations around, in some cases, even listening to the recordings.

These may be specific to areas such as folklore, religious ceremonies, traditional knowledge, and people who access the content are asked to treat the recordings with respect, even if they are, in terms of copyright law, in the public domain.

For example, a recording of a religious ceremony that a certain group specified can only be listened to by men, or people over a certain age, will be marked with sensitivity terms or guidelines. Links to this information will talk about the ethical terms of use for the collection and advise people how to treat this kind of sensitive object with respect.

However, for the British Library project members, this is all part of the great task of continuing the tradition of cultural sharing.

Ben says, ‘What’s most important is that it’s online, and further, that we are investing the time and effort to tell people how they can use these items. That access and then reuse is really vital to facilitating engagement.’

View objects from the British Library on Europeana Collections.