The power of images: Europeana Collections help students learn how visuals can be used to influence the way people think

A guest blog post by Steven Stegers, Programme Director of the European Association of History Educators (EUROCLIO)

It is often said that young people today prefer visuals over text in their education. The widespread digitization of images from the collections of museums, archives and libraries offer educators the chance to meet this preference. For individual educators the offer, however, can be overwhelming, which is why EUROCLIO in partnership with Europeana has created sets of visual sources specially selected for use in history education.

In the context of history education, students should be able to make a judgment on the usability of their sources, to be able to answer historical questions based on origin, purpose and trustworthiness. A good way of learning about these is by focusing on sources that have been created specifically to influence what people think.

The first page of the Children’s Book Vater ist im Kriege “Father is at war", 1915, contributed by Monika Schmitz to Europeana1914-1918, CC BY-SA 3.0

On Historiana, EUROCLIO and Europeana have made accessible a set of seven featured source collections that allow students to compare different ways in which visuals were used to control - or at least try to have an impact on - the population. Students can learn about how visuals are used by looking at different aspects of the visual sources. What aspects are emphasized? What aspects are left out? What does the maker of the visual source want us to believe?

What are the source collections about?

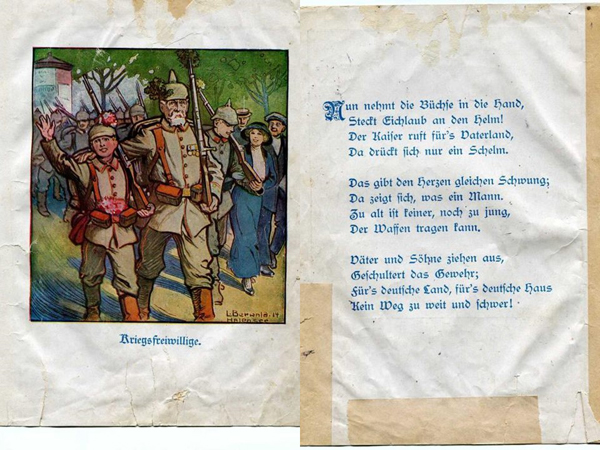

Three source collections deal with the subject of the First World War. World War One Postcards and The Visual Front show sources that initially do not seem to be propaganda but were in fact created with the intention to influence public opinion. These two source collections consist of official photographs and postcards. Another collection related to the First World War is Kinderbuch, a more biased collection of sources from a children’s book glorifying enlistment in the army during the war.

Two other source collections can be clearly understood as propaganda. Posters from the DDR and Communist China show that it is not just the message of the poster that can influence people’s opinions but also the illustration or painting style. A source collection about the Spanish Civil War illustrates the different sides within one conflict. Finally, a source collection about Suffragettes in the United Kingdom tells the development of the suffragette movement and shows visuals meant to influence public opinion, both for and against universal suffrage.

How can the source collections be used to teach history?

The source collections are very useful to make students aware that many visuals have been made with a specific purpose in mind. There are examples that make this very obvious, while others are subtler and are not immediately identified as propaganda. With this set of source collections, history teachers can help their students become more critical in real life when they find images, online or offline. The release of these collections will allow teachers to help students make a habit of reflecting critically on visual sources, by discussing the motives and purposes of visuals. And to determine what information is left out of the image.

All the featured source collections here can be found on Historiana.

Join the conversation on Twitter via #Europeana4Education