Since the DE-BIAS project began in January 2023, project partners have been engaging with different communities to gather knowledge for the development of a new vocabulary which will sit at the heart of the DE-BIAS tool. The vocabulary is born out of collaboration and co-creation sessions with relevant communities, reflecting the project’s commitment to examining problematic language and enhancing cultural heritage metadata in three realms: ethno-religious identity, gender and sexual identity and colonial past.

As part of this work, the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision (NISV) has embarked on a collaborative journey with members of the Dutch Surinamese community. Over three sessions, participants delved into archival materials, refining descriptions and infusing metadata with accurate and inclusive language. The group was diverse, spanning different ages, professions, and cultural backgrounds, and our facilitating community member Sharma took the lead in the sessions.

Refining and adding terms

During these sessions, participants introduced numerous new, relevant search terms, including place names, company names and cultural terms related to traditional dress, foods, rituals, and religion. For instance, while analysing a Polygoon Journaal (collective name for Dutch newsreels) clip depicting the Central Market of Paramaribo, participants recognized the traditional dress of women, noting down terms like 'orhni,' 'koto,' 'angisa' (anisa), 'pangi,' and 'sari' to be added as search terms.

This highlighted significant gaps in the existing descriptions of the material shown, which in turn demonstrated the value of co-creation sessions in enriching descriptions to be more searchable and accessible to the relevant communities. Incorporating such cultural aspects and knowledge into the metadata will make previously absent information visible and discoverable.

Contextualising language and history

Discussions surrounding the clip also revealed a preference among participants for contextualising offensive language rather than outright replacing it. As Sharma put it: ‘People get it, things change over the years, but explanations do need to be given as to why it was written that way back then... I think that addition is a lot more important for understanding and for searching [than alteration]. It's like history books: you can't rewrite history, but you can always apply that kind of addendum or add to it.’

As such, participants favoured retaining original outdated terms for population groups depicted in historical footage, followed by a statement acknowledging current terminology.

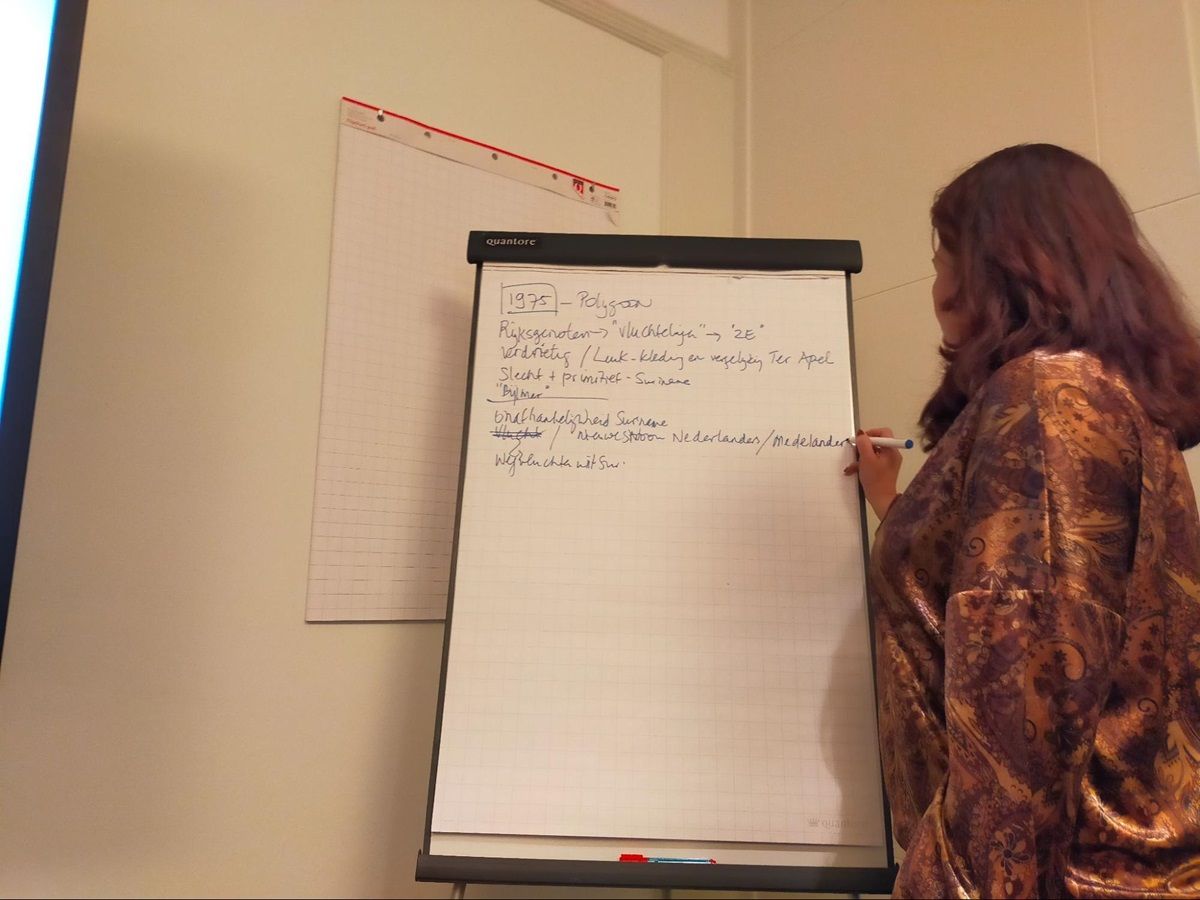

Another example arose during the analysis of a Polygoon Journal from 1975, documenting Surinamese migration to the Netherlands. Participants identified a historical inaccuracy in the description, which attributed the mass migration solely to ‘growing unemployment’ in Suriname. The participants pointed out that this description overlooked the socio-political turbulence and ethnic tensions precipitating this wave of migration. They described political upheavals, economic disparities, and social unrest as important migration catalysts. Their insights corrected historical inaccuracies and foregrounded lived experiences, enriching the archival record with multifaceted truths.

Reflecting on this, Sharma feels the sessions showed how much we are still learning now from the shared history between the Netherlands and Suriname: ‘It was beautiful to see that the younger and the older participants knew how to find each other in this group, that we all learned a lot among ourselves. Not only you [NISV] from us, but also we from each other. It was beautiful to move from all those emotional responses to the descriptions and from there discover, “okay, well this is missing and that needs supplementing.” That's a really nice conclusion to all those sessions. A bit of storytelling culture!’