Good news for digital innovation

So the good news is that Europe is a world leader in digital heritage innovation. European Union (EU) digital cultural initiative Europeana consists of a thriving network of close to 4000 memory institutions (libraries, museums, archives etc.) who have shared over 50 million digitised objects in a standardised format on the digital platform. This model, based on open standards and an inclusive, distributive approach, is being adopted as a model in the US and Japan to Brazil and Canada.

Ten years ago, the EU made a bold decision about our cultural heritage. They deemed it too important to leave to market forces alone. Two weeks ago, Europeana’s public evaluation has shown that it is still very relevant to the challenges we are facing today in Europe and the EU has recommitted its support to the initiative.

A challenge for audiovisual archives

However, we are facing some serious challenges and unfortunately, these affect audiovisual (AV) archives more than any other creative medium.

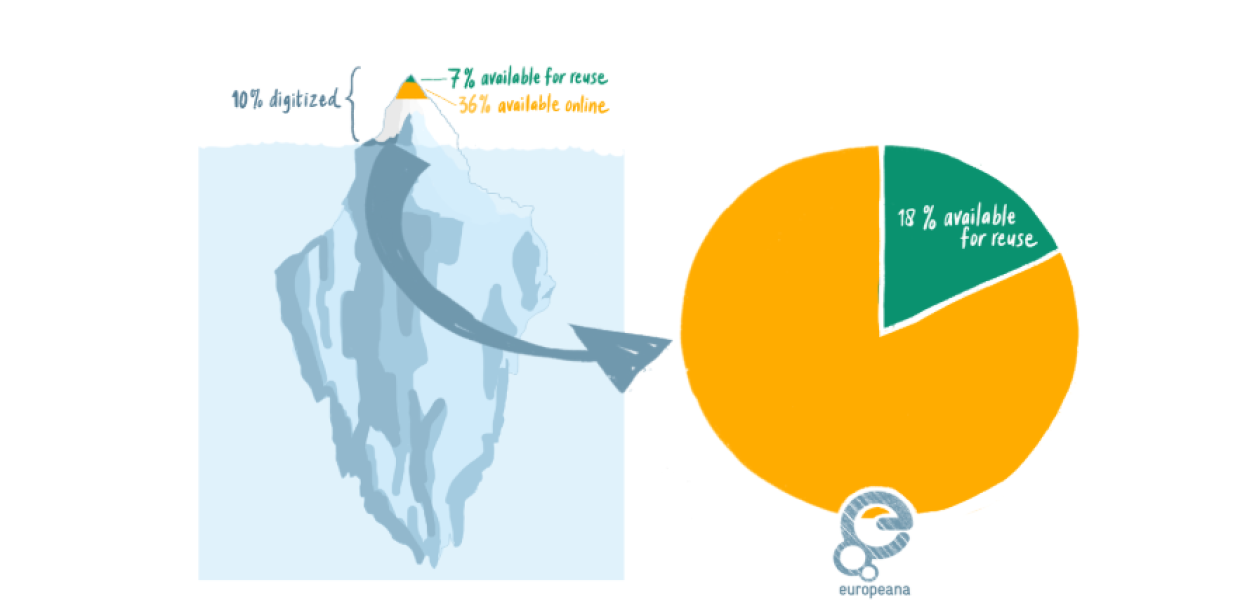

Here is the issue: we have currently digitised around 10% of all our heritage. Of that 10% (which represents around 300 million objects), only about one third is available online, and of that, only 7% is available for reuse. At Europeana, we work very hard to improve this equation and as you can see almost 20% in Europeana can be shared, adapted (all within full respect of copyright of course) while the other 80% can at least be viewed online.