Choosing a country's artworks for Europeana 280: Estonia

This month, we’ve started highlighting some of the works nominated as part of Europeana 280 in preparation for the launch of the campaign next month. On Europeana Art History Collections, we’ll showcase treasures from a different country each week, and if you download the popular app DailyArt, you can enjoy a Europeana 280 artwork every Tuesday and Sunday in March.

We’ll also continue this blog series, finding out more how different countries went about making their choices. Here, Europeana 280's Exhibition Coordinator Ann Maher looks at Estonia’s nominations.

Artistic responses to turbulent political times have been referenced by several countries nominating artwork for Europeana 280 but are a particular feature of the selection from the Republic of Estonia. The aftermath of the First and Second World Wars and Soviet occupation in the 1940s had a profound impact on artists and provide the context behind many of the selections.

The Ministry of Culture coordinated the process and nominations cover a wide range of periods and styles from different institutions. From the 15th century, there is a monumental fragment of a Danse Macabre – the dance of death. There are also examples of academicism, social realism and symbolism and from the second part of the 20th century, Pop art and concrete poetry. Some of the nominated artists went on to play significant roles in the development of both domestic and international art institutions. So what treasures can we expect to find in the Estonian selection?

Heritage heroes

Painter and illustrator Kristjan Raud is a key figure in Estonia’s art history. He was a strong advocate for the preservation of national culture and a separate museum dedicated to folklore. In the 1930s, he illustrated Kalevipoeg, the Estonian epic poem. In his symbolist triptych, The Maiden of the Grave (1919), the Art Museum of Estonia notes how Raud interpreted mythological content in a modern and political way to reflect the era in which he was working: “It was a time when Estonia was fighting for its independence against two major powers – Germany and Russia – and it creates the image of a small nation’s eternal existential striving for survival.”

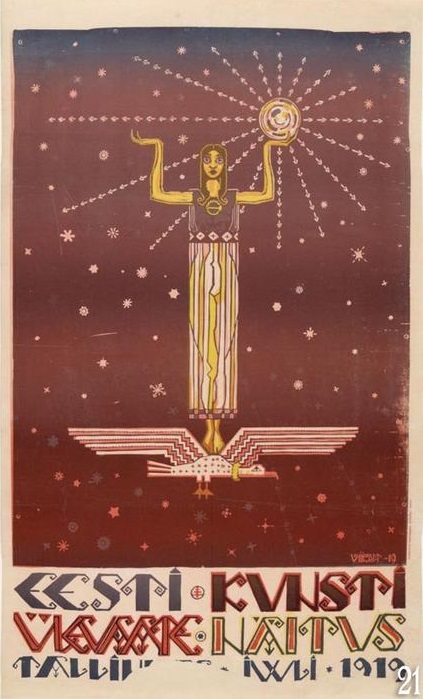

Poster ‘Survey Exhibition of Estonian Art’, Conservation Centre Kanut / Kadriorg Art Museum, CC0

Battles on the eastern and southern fronts at the time of the Estonian War of Independence did not hold back cultural life in the Estonia’s capital Talinn. In the summer of 1919, an exhibition featured more than 400 works by 49 artists. Estonia’s most famous graphic artist, Eduard Wiiralt designed the poster and while the difficult times are reflected in the paper’s poor quality, the artistic level remains unaffected.

The aftermath of the First World War, followed by the Estonian War of Independence didn’t stop artistic activities. Graphical artist Eduard Wiiralt, was studying in Tallinn in 1919. He was born in St Petersburg to parents who worked on a Russian country estate, and moved to Estonia with his family, but his formative years as an artist were spent in Paris. He died there in 1954 and is buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery. His works focus on the dark aspects and fears of human nature and the hallucinatory qualities of his graphical creations have been attributed to drinking excessive quantities of absinthe, a potent spirit that was a part of bohemian life.

Explosive colour

Artist Konrad Mägi was also in Paris for a while and part of the Estonian colony in Montparnasse. Impressionism and Fauvism were influential on his use of colour and he later turned to expressionism. Mägi was famous for his landscapes but also his sensitivity to societal tensions. The Art Museum of Estonia chose a Post-Impressionist work that highlights both of these aspects. In Landscape with a Red Cloud (1913-1914): “Mägi uses his exceptionally unique artistic style and explosive colour palette to create powerful, emotional images in politically disturbed times.” When Estonia achieved its independence after the First World War, Mägi became a significant figure in the Tartu art scene and was the first director of the Pallas art school that became the training ground for dozens of Estonian artists.

Another vivid selection from the Tartu but this time from the 1960s, is a dazzling Pop art work from ‘the grand old lady of Estonian art’, Malle Leis. She originally trained as a scenery artist and was a member of the creative group ANK ’64. In a recent exhibition, the museum described the role of nature in her life, whether in oil paintings, watercolours or silkscreen painting: “Flower and plants lead their own very vital life, in places even more vital than people.”

We look forward to sharing more art selected for the Europeana 280 campaign soon. In the meantime, follow the conversation on Twitter via #Europeana280.