Choosing a country's artworks for Europeana 280: Croatia

Last week saw the launch of Europeana 280 with the start of the brilliant #BigArtRide tour in The Hague and Brussels, and the first part of our new virtual exhibition Faces of Europe, showcasing beautiful artworks from every country taking part.

As art lovers across Europe begin to explore the over 300 fascinating works contributed, we continue this weekly blog series, delving a little deeper into each country’s selections. This week, Europeana 280’s Exhibition Coordinator Ann Maher highlights nominations from Croatia.

Croatia joined the EU in 2013, although with its unique natural and cultural treasures, it has always been a strong part of Europe. Nominations for Europeana 280 reflect several periods of vivid and complex history but particularly focus on contemporary work from the many groups active in the second half of the 20th century. The Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Croatia - as the national aggregator for Europeana - coordinated the nominations by inviting Croatian cultural institutions to join the project.

Benković and the Baroque

The Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts Strossmayer Gallery of Old Masters was opened on 9 November 1884 with 256 works from Bishop J. J. Strossmayer. From its collection comes a work Abraham’s sacrifice of Isaac painted in 1715 from a late Baroque Dalmation painter, Federiko Benkovíc. This big composition shows how Abraham, in carrying out God's mission to sacrifice his own son, is stopped at the last minute by an angel. The painting is one of four compositions that Benković, ‘the last great Schiavone’, painted in 1715 for the Schönborn castle in Pommersfelden. It was purchased for the Strossmayer Gallery at the London art market in 1936.

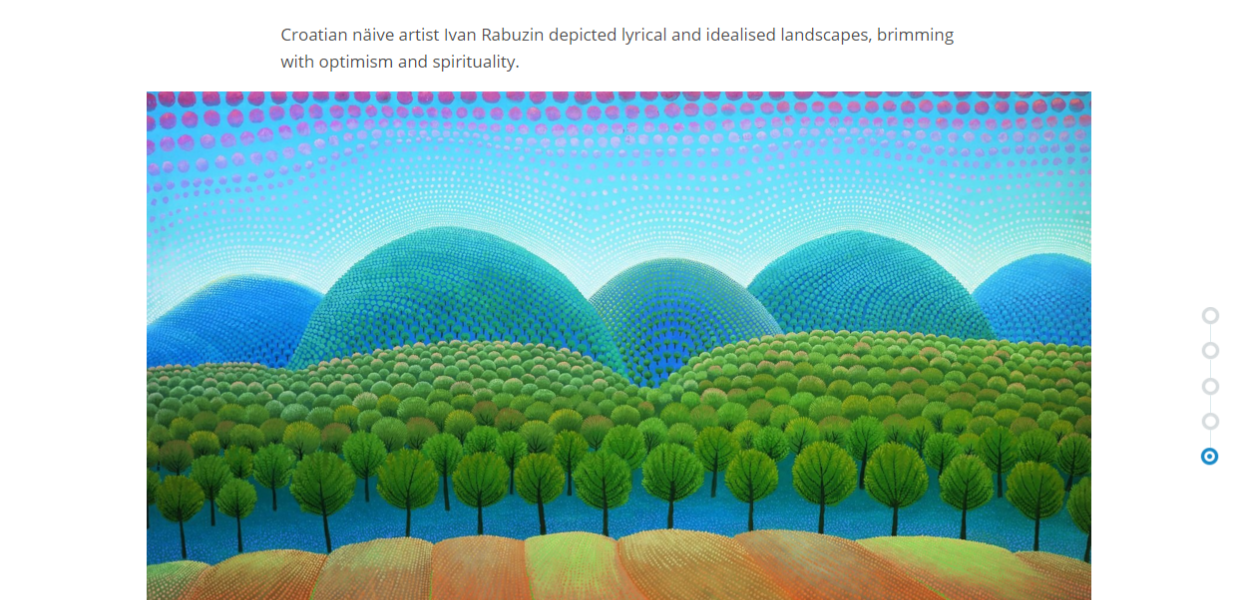

A screenshot of a Croatian work featuring in the introduction to Faces of Europe, our new virtual exhibition. A new part of the exhibition will be launched every two weeks until July.

Early avant-garde

Marino Tartaglia (1894-1984) was one of the painters who introduced the avant-garde into Croatian art. Born in Zagreb, he left for Italy in the turbulent times before the First World War and studied and worked in Rome, Florence and Paris. After returning home in 1931, he began to teach at the Academy of Fine Arts and enjoyed a long career, participating in hundreds of exhibitions including the Venice Biennale of 1940. The Museum of Contemporary Art describes their selection of his Autoportret (1917) as ‘an exceptional example of expressionism in Croatian painting’.

The architect and painter Josip Seissel was an urban planner, but under the pseudonym Jo Klek, also participated in avant-garde movements around the Group Travelers and Zenit magazine. His painting Pafama (1922), another selection from the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb, is considered to be the first abstract composition of Croatian modern art and has been described by them as their ‘trademark’.

Croatian art on the international stage

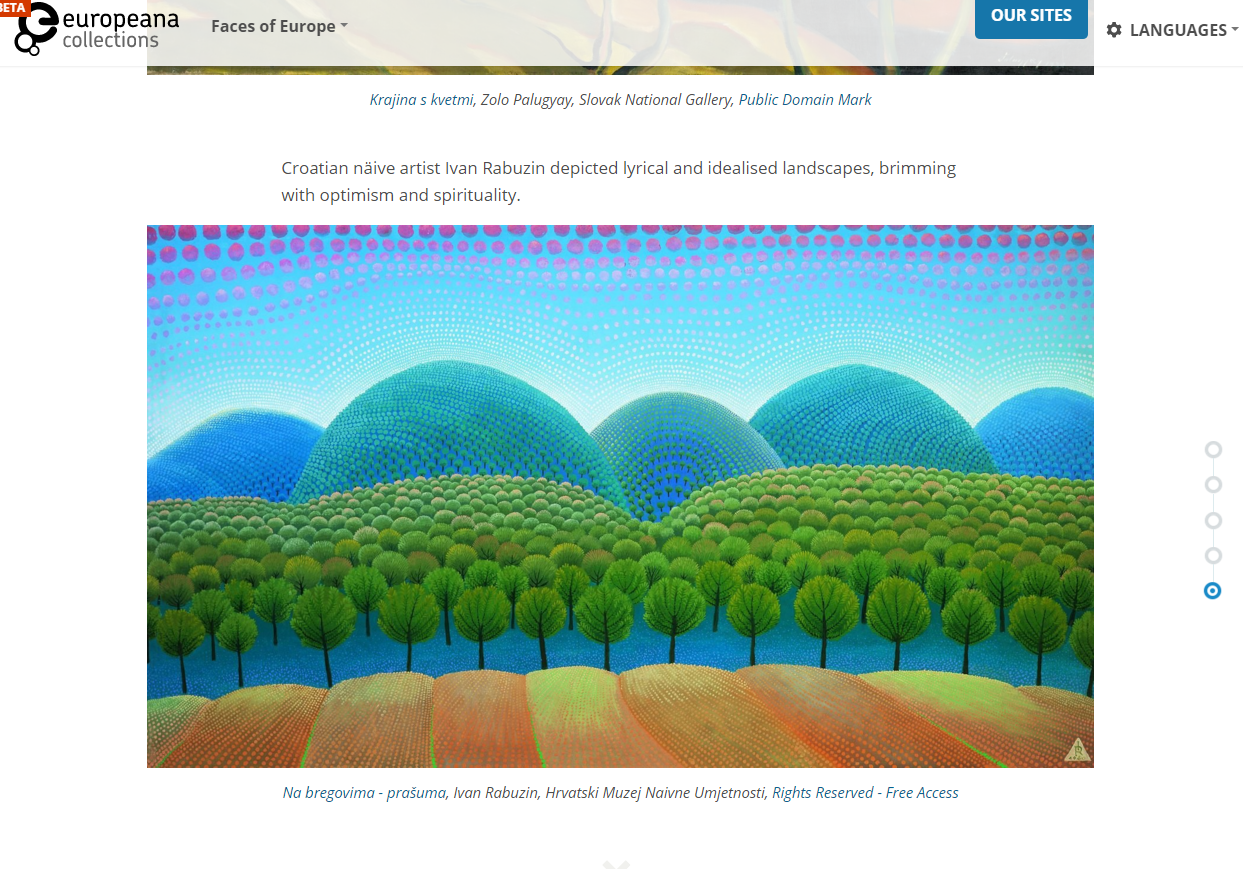

Naive art plays a special role in Croatia’s art heritage. The Croatian Museum of Naive Art, opened in 1952, is the first museum institution in the world that was founded to record, collect, study and present this form of art. A group of artists from a small village on the border of Hungary, which became known as the Hlebine School, attracted international recognition. Ivan Rabuzin is a painter of lyrical and idealised landscapes, founded on the sequencing of circles or circular forms, brimming with optimism and spirituality. His unique style and the distinct modernism of his visual expression has been recognised and appreciated on a worldwide scale, used for theatre curtains in Japan and even tableware, including a line designed for famous manufacturer Rosenthal.

Exat 51 and Gorgona

Artists of the 1950s who wanted to put some distance between officially sanctioned styles, such as socialist realism, and their own artistic freedom, included members of the Exat 51 Group. In their manifesto, they declared that ‘nonfigurative or so-called abstract art are not expressions of decadent aspirations’. Ivan Picelj was a founder member and a key work from his participation in the group - In Honour of El Lissitzki (1956) - is a Europeana 280 selection: an homage to Lissitzky, an important figure of the Russian avant-garde.

Another 1950s collective, but of a completely different nature, was the Gorgona group. Although they held exhibitions (Studio G) and published an ‘anti-magazine’ (11 editions, including one by British writer Harold Pinter), these didn’t follow conventional patterns. There was no artistic manifesto and the work of each individual artist (whether painter, sculptor or writer) remained distinct. The shared ideal was the freedom of art. Painter Julije Knifer (1924-2004) was a member, and the Europeana 280 nomination Meander (1960), is an example of his repetitive (and from 1960, single) artistic motif, where form and content were reduced to a minimum. Knifer referred to them as anti-paintings.

Their more unusual forms of communication or ‘Gorgona behaviour’ such as sending invitations – please attend – but without giving a place or time, reflect the legacy of Dada. An exhibition of Gorgona work was held in February 2016 in Zurich as part of the city’s year-long program to mark Dada’s centenary in the city where it started. If the aims and intentions of Gorgona are complex, the same applies to Dada, as in their famous saying: “Only Dadaists know what Dada is. And they don’t tell anyone.”

You can discover each of Croatia’s thought-provoking nominations on Europeana Art History Collections – tell us which you like best using #Europeana280.