Lela Harris is a British Mixed Heritage, self-taught artist, who found an audience - and her first professional commission - through sharing her work on Instagram. Lela describes her first commission working on the Folio Society’s first illustrated version of The Color Purple by Alice Walker as a ‘dream come true’. The work saw Lela become runner-up in the V&A Illustration Awards 2022 for her cover design. Following this success, Lela won a second commission called ‘Facing the Past’.

Facing the Past

The city of Lancaster, in the north of England, was the fourth biggest slave trading port in the UK during the 18th Century, something that few of its current inhabitants are aware of. The Judges’ Lodgings Museum, along with Lancaster Black History Group, two local universities, the city council and the museums service, set up ‘Facing the Past’ to explore this side of Lancaster’s history. The museum has several portraits of the elite of Lancaster who financially benefited from the slave trade, but no portraits of the enslaved Africans who came through Lancaster. The ‘Facing the Past’ project looked to redress this imbalance.

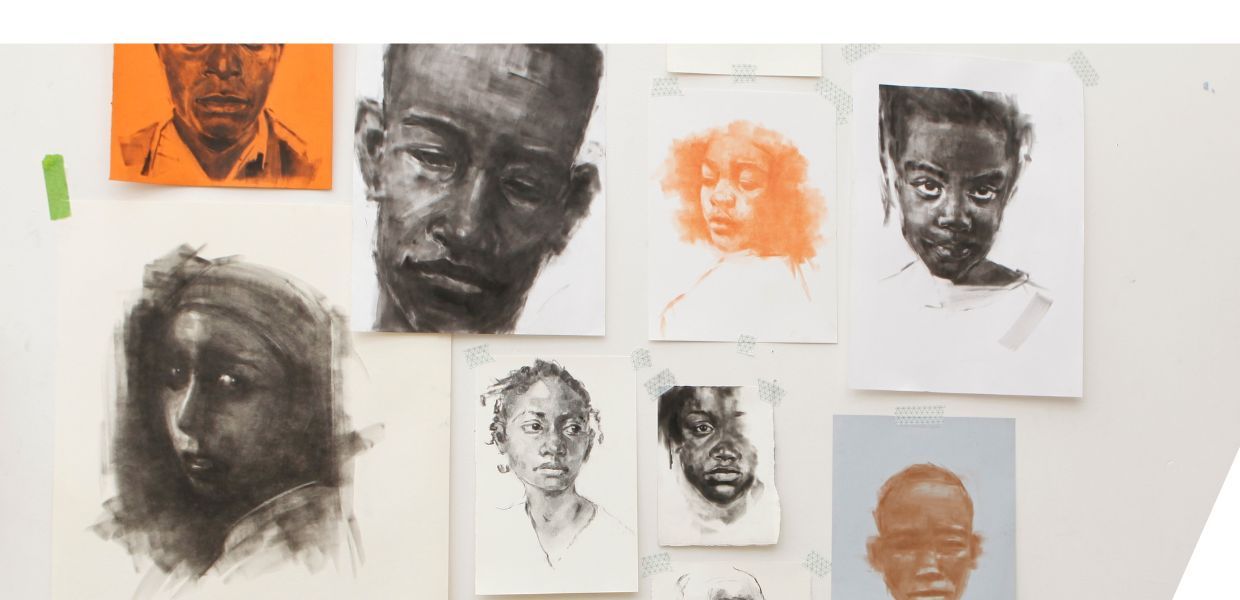

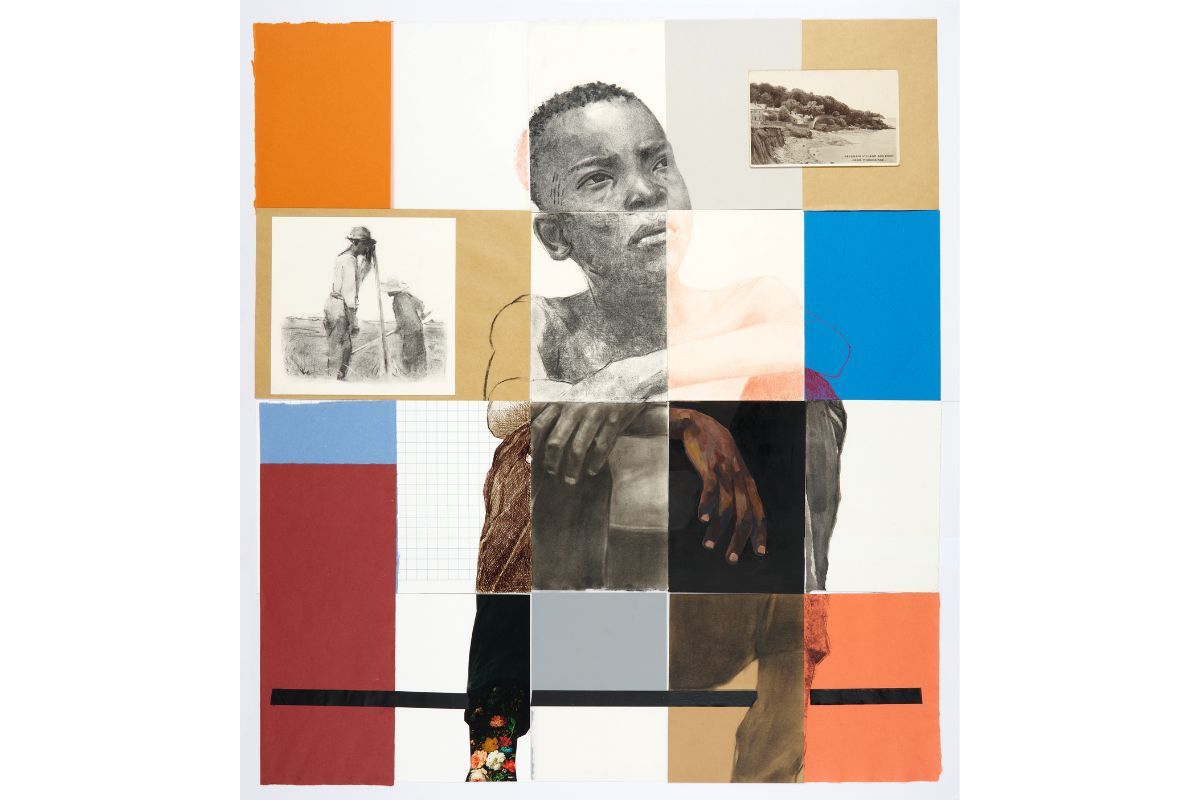

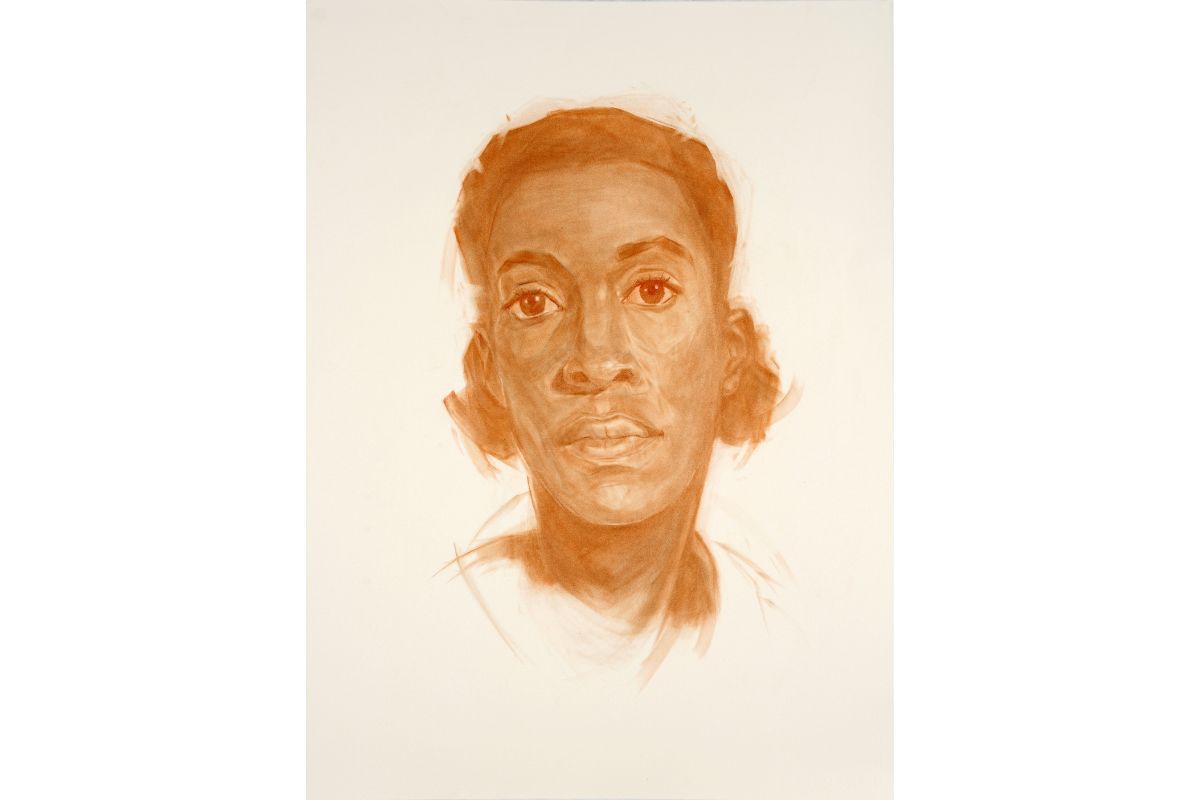

Lela Harris was commissioned to use historical records and her creative processes to develop portraits of four enslaved Black Africans who came through Lancaster during the 1700s.

Fragments of historical fact

But how do you create portraits of people for whom you have no visual references?

Lela says, ‘Initially, I spent as much time researching the subjects of the portraits as I did drawing and painting because I wanted to get to know them as individuals before I thought about what they might look like. For each portrait candidate, I developed a fact sheet. I looked at what was fact, what was conjecture, what connections could be made to other portraits within the museum, and noted down the creative thoughts I had for each of the individuals.’

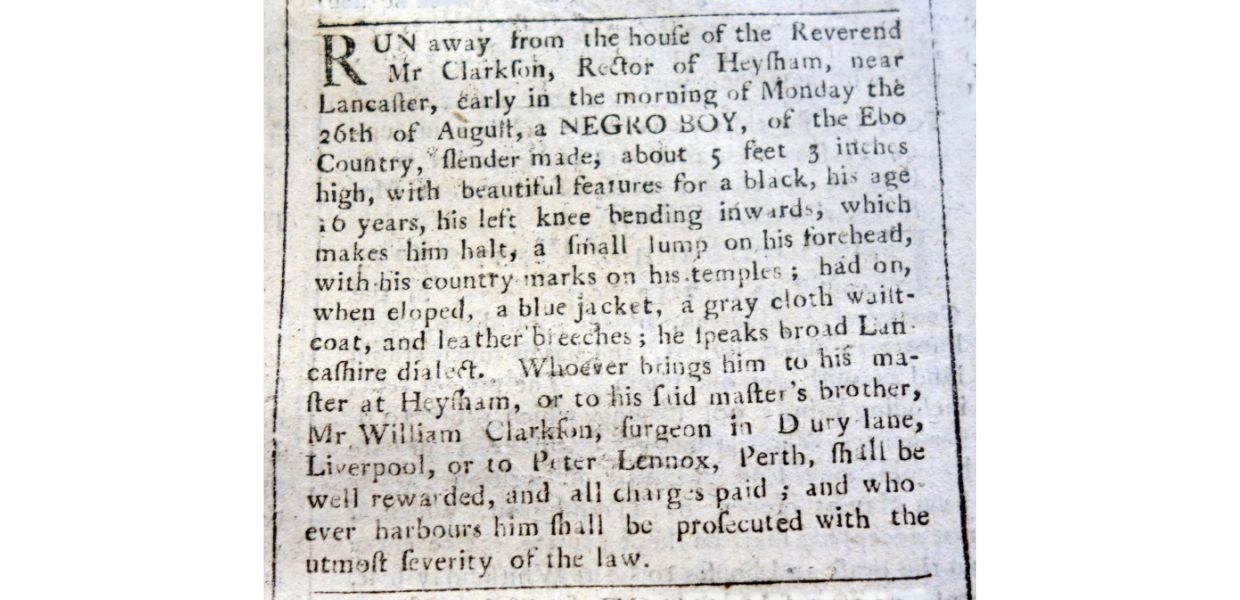

Using baptism and burial records online, Lela found information about 39 Black Africans who came to Lancaster. Some of those enslaved Africans ran away from their owners, and the Runaway Slaves Database from Glasgow University offered up clippings from newspaper adverts about them.