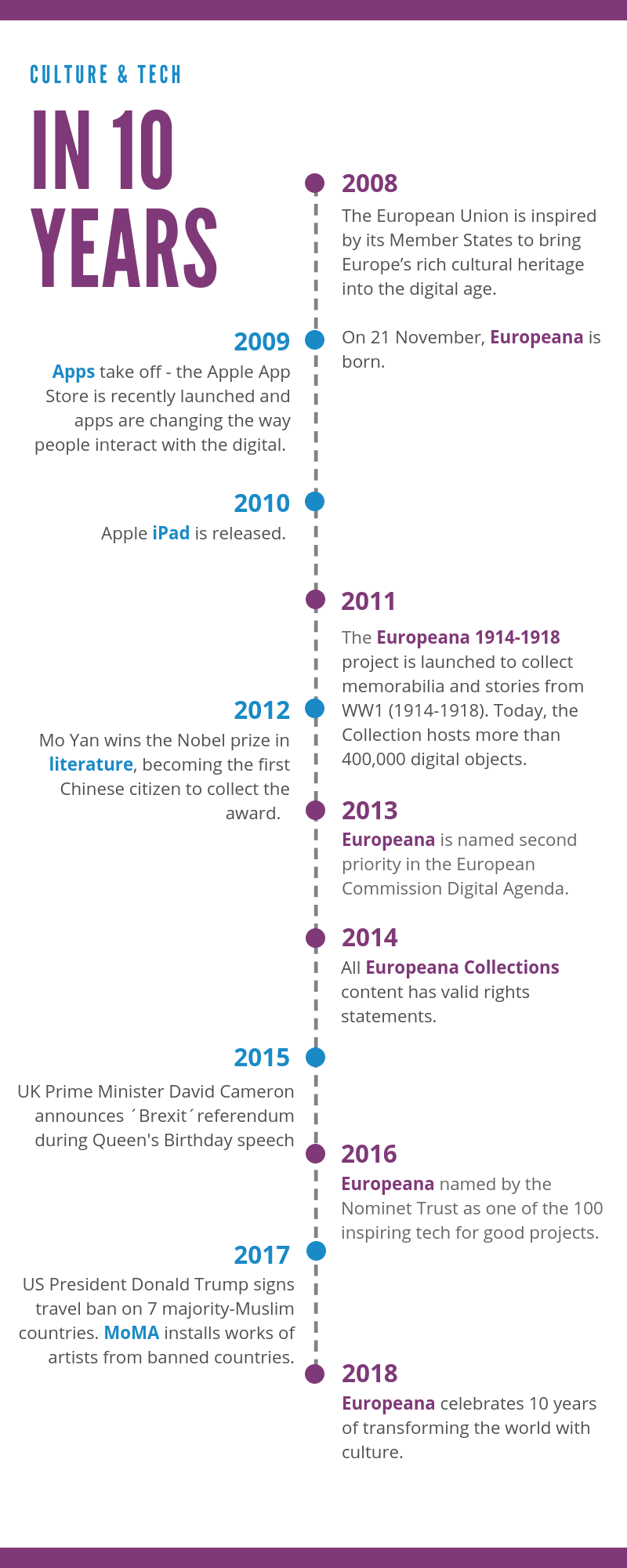

10 moments in 10 years of culture and technology

In today’s article on the topic of 10, we look back at the last ten years of social, cultural and tech innovation, and draw parallels between the cultural zeitgeist and Europeana activities.

2008: Ten years ago, tech was becoming sophisticated and far more ingrained in society - in our behaviour and in our daily lives. Google launched Chrome and mobile voice search, advertising grew in apps and other platforms and Twitter usage became mainstream.

Advertising became sophisticated, as tech giants started to play with new ways of reaching and persuading markets recovering from the global financial crisis.

At this same moment, the European Union was inspired by its Member States to bring Europe’s rich cultural heritage into the digital age away from the influence of private market forces. Europeana was born.

Europeana Collections started with approximately 2 million items in its collection (this has now grown to more than 58 million) and so the transformation began.

2009: Tech giants were now a household name. While we were previously familiar with their brands, they were increasingly finding their way into our everyday lives.

With the launch of the Apple App Store and the mainstreaming of smartphones, society was increasingly hooked to a gadget.

Meanwhile, Europeana launched the PrestoPrime project which would revolutionise the preservation and storage of digital media objects, integrating these records and media archives into the European digital library.

2010: iPads, e-readers and 3D technology - welcome to 2010. That was the year that Apple launched the iPad, making social media more accessible and interesting than before. Micro-blogging started trending, with Twitter and YouTube shifting away from traditional modes of production and consumption.

In comparison, Europeana focused on a promotion of tech initiatives that exemplified social responsibility, values and social consciousness, the Heritage of People’s Europe (HOPE) project.

The project aimed to collect cultural heritage items under themes of the emancipation movement, environmentalism and equal rights for immigrants, amongst a few. The project collected some 850,000 items from posters to films.

2011: 2011 was a huge year for world events. Globally, major political, military and terror events took place. The world was struck by a series of environmental disasters. Occupy Wall Street protesters took up their place and the year was marked by a greater sense of loss than usual.

The tech world mourned the loss of Apple’s Steve Jobs, and protestors in the Arab Spring were lauded for using social media to mobilise - in a truly exemplary show of technology ingrained in the human consciousness.

Europeana projects in 2011 would highlight the humanity in traumatic events, and the human stories in times of adversity. The Europeana 1914-1918 project held its first collection day in Germany, creating a space for the personal stories from everyday Europeans as they related to all sides of World War One.

Unbeknownst then to the project partners (Europeana Foundation, the University of Oxford and Facts & Files), 1914-1918 would turn into a major pan-European collection which now hosts more than 600,000 items and became Europe’s largest online resource on World War One and lead to the incredible Transcribathon initiative (more on that in 2016) and celebrated in media globally.

2012: Perhaps in backlash to the darkness of 2011, the world seemed to share in a general sense of uprising. The arts, films and literature spotlighted corruption in militaries. In the US, big businesses like Goldman Sachs, Apple and MacMillan and in India, the government, all faced major backlash over unethical or fraudulent dealings. Southern Europe faced mass protests against the Eurozone Crisis.

It was a year of social upheaval and rebellion.

Europeana content too took on a revolutionary new endeavour - the Europeana 1989 project. Taking a pan-European perspective in the lead up to the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, the project focused on collecting and highlighting objects, videos, photos and stories from this revolution ary period, showing the changes to Central and East Europe through the different perspectives of those affected.

2013: The world began to see the true power of technology and social media - with some instances more virtuous than others. US Police departments used social media to capture Boston Bombing suspects and civilian journalists in Syria used mobile phone images to show apparent chemical attacks on civilians. The major story of the year, however, came from former CIA employee Edward Snowden, who stole and leaked thousands of classified documents alerting the world to the major surveillance schemes.

At a political level, the European Commission highlighted their priority towards harnessing technology for good. As such, they named Europeana as the second priority of the new Digital Agenda (2013-2014).

At the time, the European Commission stated, 'The digital economy is growing at seven times the rate of the rest of the economy, but this potential is currently held back by a patchy pan-European policy framework. Today's priorities ... place new emphasis on the most transformative elements of the original 2010 Digital Agenda for Europe.'

2014: There were a number of big technological steps in 2014 - from the European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission leading the world’s first comet landing to advances in AI and virtual reality technologies, with the advent of a robot with in-built agility and the mainstream sale of the Oculus Rift.

At Europeana, the focus was also based on changing technologies and user needs. Amongst a number of new initiatives, this would mean the election of the first Europeana Network Association Members Council. The election solidified a commitment from Europeana to an open and collaborative operational approach that was cemented in an empowered Network of cultural heritage professionals.

2015: The year was host to events that touched the world, and social media became a space to share views in a symbolic way with the advent of specific display picture filters (for example, rainbow flags in celebration of marriage equality, or je suis Charlie and the French national colours in commemoration of the deaths at the Charlie Hedbo headquarters).

Europeana grew and increased its strategic focus for the 2015-2020 period. In furthering its previous agenda of user-autonomy and empowerment, areas identified were those which would lay the foundation for Europeana today: A vision which included a transition from portal to platform ('portals are for visiting, platforms are for building on'), improvement of data quality, accessibility, discoverability and reuse, and the development of the first thematic collections in Art and Music.

2016: Changes to US and UK government policies heralded a transition period that mobilised political and social perspectives from both sides of the spectrum.

Driven to continue connecting to the human stories behind adverse times, Europeana launched the Transcribathon initiative. The digital tool relies on the unique skills of the community - teams of school children to pensioners - who compete together to transcribe documents from World War One collected during the aforementioned 1914-1918 collection so that they can be digitised, and translated for all to access and read.

You can read more on Transcribathon from project partner Frank Drauschke here.

Thanks to initiatives like these, Europeana was named by the Nominet Trust as one of the 100 inspiring tech-for-good projects for providing better access to knowledge and fostering understanding, knowledge and cultural value in society.

2017: The general public were increasingly empowered by technology. There was an increase in techno-literacy, and the concept of being critical against social media, news agencies and other tech-mediated spheres was cemented. AI and augmented reality technologies felt more accessible than ever before.

Already operating with the technical end-user in mind, Europeana was named the best data API for REST API technology at API World 2017. The REST API is a digital tool that allows people to build applications that use the cultural heritage objects stored in the Europeana repository.

2018: And now for Europeana? In 2018 we celebrate the end of an era and the beginning of something exciting and new. The time has come to be bold once again. We must take inspiration from the visionaries of 10 years ago. We must feel pride from the actions, successes and hard work of those over the past ten years. And we must once again commit to safeguarding Europe’s cultural heritage - preserve it, innovate it, and uphold the humanist values and perspectives that sit at the heart of Europeana.

This article is a part of the Europeana Anniversary series - 10: legacy and moving forward. Keep up-to-date with all of the anniversary content we will be releasing on Europeana Pro and Europeana Collections, either here or on Twitter. #Europeana10.