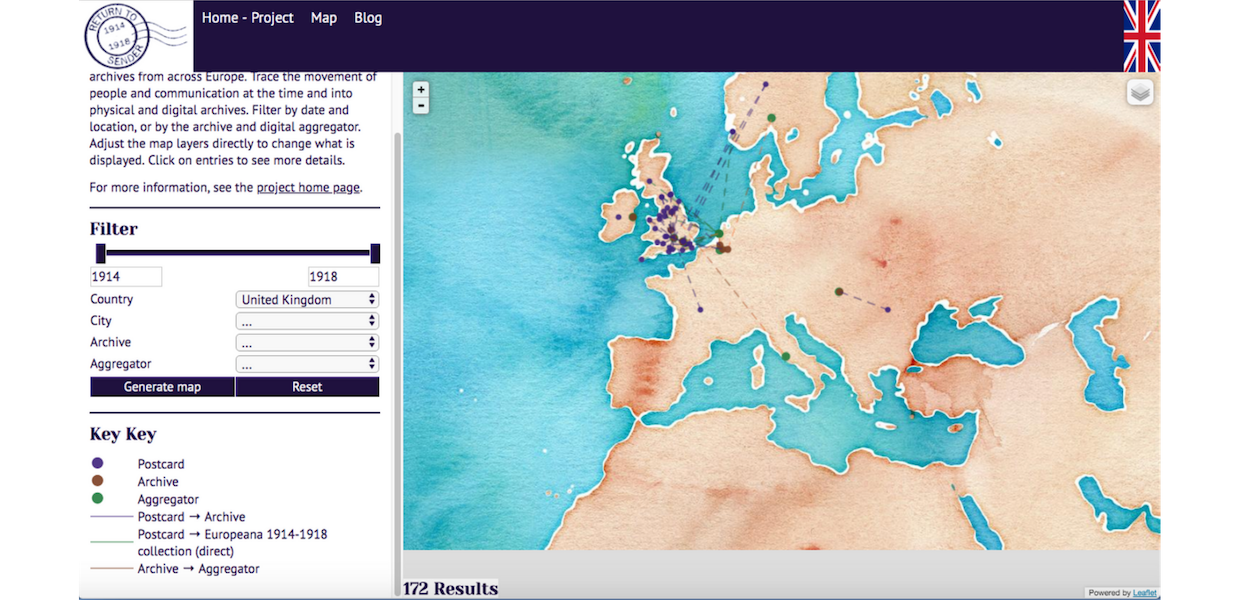

The above GIF shows a sample of filtered results on the interactive map ‘Return to Sender: Mapping Memory Journeys in the Europeana 1914-1918 Postcard Archive’. CC BY-SA

How did you discover the Europeana Grants Programme and why did you decide to apply for it?

I was previously aware of Europeana Collections as an essential digital platform for the exploration of artefacts across cultural heritage institutions, having used it for both teaching and research in the past. I also follow Europeana Research’s Twitter account, which is how I came across the call for projects for the Europeana Research Grants Programme. The theme this year being WWI immediately piqued my interest, as my PhD thesis — then published in the form of a book — focused on Dada and Existentialism, a transnational art movement contemporaneous to the war, and a post-WWII philosophical movement, respectively. I was also involved at the time in conferences surrounding the centenary of WWI. As part of my role at Coventry I teach modules in French history, and this involves visual imagery from the early 20th century, so I imagined the project would feed directly back into my teaching as a pedagogical tool, as well as its goal as a tool for research. I decided to apply to the programme for these reasons, but also because I have a particular interest in postcards and what they have to reveal about socio-cultural and political developments of the period.

How does access to digital cultural heritage influence your research?

The First World War’s global nature significantly complicates its study because of the dispersal of its remaining artefacts. Often it is simply impractical to access physical archives; it can also be the case that original pieces belong to family collections or have simply been lost. Moreover, in a museum setting, resources are curated, imposing a specific ‘memoryscape’ or politics of memory of a particular period. Digital cultural heritage allows a contemporary researcher to overcome issues of physical accessibility, as well as occasionally offering a substitute or ‘copy’ of artefacts that would otherwise be unuseable. Through their browsable resources, platforms such as Europeana Collections, confront the issue of data bias inherent to curation by putting more power in the hands of the user.

Digital cultural heritage will be particularly important as we move temporally further away from periods such as WWI, after centenary commemorations have finished. Additionally, shifting patterns of international relations, environmentalism and digital fluency will give increasing space to digital communities. I am interested in the ways in which these developments impact memorialisation, a key aspect of my ongoing research.