Europeana 1914-1918: Showcasing Crowdsourcing and User Generated Content as The 'New' History

This article by Dr Stephen Bull is the first in a three part series about crowdsourcing.

There is a genuine case to be made that, in the digital age, 'User Generated Content' (UGC) is 'new history'. Its beauty is twofold: much of it has never been shared outside of a family or personal context, and now, being seen publicly for the first time, it can be marshalled into categories and mined for research.

Such projects may relate to known historical events and themes, or to stories hitherto unrealised. Documents and ephemera captured could otherwise be lost entirely with passage of years, or never fall within collecting policies and resources of cultural institutions.

The UGC concept fits modern aspirations for electronic data, rapid searches, and instant accessibility. Moreover, unlike many documents and photographs in public archives, items uploaded onto the internet by private individuals do not usually deal with the business of states and authority. They are rather the primary source material of the social and family historian, the 'everyday documents' of the everyman.

Regimental certificate of Lieutenant Arrigo Montorsi (1896-1951) of the Italian 16th Infantry who served in the Balkans and elsewhere. Just part of a group of personal items contributed on behalf of Silvana Montorsi.

Europeana 1914-1918 illustrates this point perfectly. Its wealth and breadth is undeniable: a single click generates close to 400,000 results from across Europe, and well beyond. Though the core collections are uploaded from libraries and archives, the public has also contributed 14,000 'stories'. These have been provided by individuals, or contributed at 'Roadshow' events with assistance from volunteers and professionals from the library, archive and museum sectors.

Many of these ‘stories’ are data packets containing many pages of information: copies of documents, letters and postcards, photos of three dimensional objects and video. Others comprise a poignant single image. Random illustrations of richness and diversity include everything from a message in a bottle deposited by a German workman under concrete foundations in August 1914; to a collection of teddy bears carried into battle by British officers as talismen; the remains of a Mannlicher rifle from the Isonzo front; and a number of substantial, but hitherto unknown, diaries from different countries.

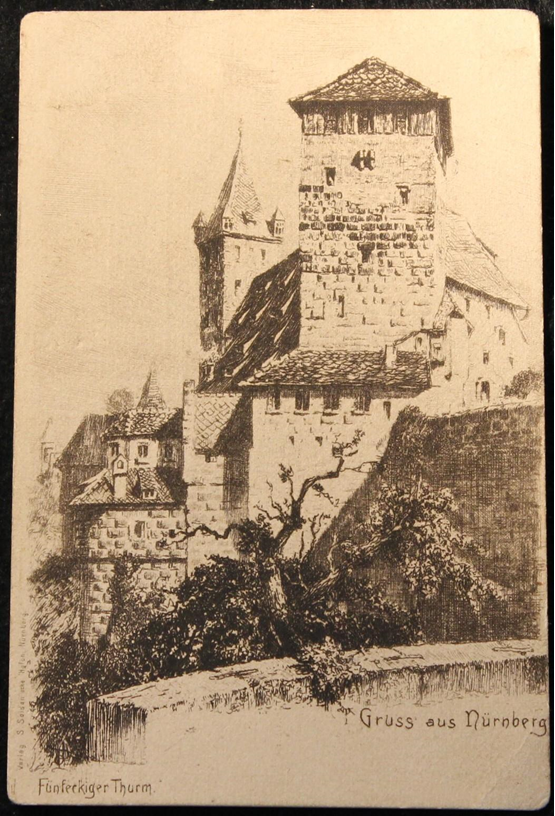

'Greetings from Nuremberg', postcard from a future dictator: Dear Lanzhammer, I am now in Munich with the Ersatz Battalion. Currently I am under dental treatment. By the way I will report voluntarily for the field immediately. Kind regards A. Hitler 19.12.16 Contributed to a Roadshow in Munich.

As Europeana 1914-1918 has shown, the creation of a virtual UGC archive has many benefits, including the relatively modest resources needed to create and preserve a collection and the inclusive nature of a 'crowdsourced' or 'community archive', where users self-select what it is about an historical theme which interests them. Items are 'shared' in a way that chimes with popular social media, but within a space dedicated to a subject area.

New users, and the public in general, are introduced to the established collections accompanying the user generated content in a way previously impossible. The 400,000 World War I items can be compared to the somewhat over 30 million digitised items that 2,300 institutions have uploaded to the various other Europeana archives and projects.

Framed medals and photograph of Harry S Green, of 4th Battalion Black Watch (Royal Highlanders). One of a group of associated items including letters and cards, contributed by Clare Sanderson.

Though there is broad data on 'hits' we may never know exactly to what degree the Europeana UGC is shared and viewed by interest groups, families separated by distance, and general browsers, or precisely what items are used for which research project. However it is already possible to illustrate some specific outputs.

For example images have been used in articles, and material used to inspire a Lancashire schools project with the support of the University of Oxford. A batch of 'curated images' drawn from ten European countries now appears on Wikimedia Commons.

Arguably however the greatest test of historical usefulness comes when creating new works based mainly upon UGC content. The first attempt, by BBC Journalist Jackie Storer, was published in printed book form by the British Library in association with Europeana, as Hidden Stories of the First World War (2014). Taking 32 promising family tales, most of them from the database, Storer re-interviewed many contributors and cross referenced their testimony with official documentation and other works.

The act of producing Hidden Stories exposed the pitfalls, sheer hard work, and circumspection required when using UGC as raw material. Imperfect memories of veterans and families, the 'Chinese whispers' of gossip, national bias, or simple vagaries of translation often confirmed that 'family story' and 'historical fact' are far from one and the same, and that using UGC profitably requires perhaps even greater effort than 'ordinary' archival data.

Jožetu Lajnšiču, a Slovenian machine gunner fighting on the Eastern Front with the Austro-Hungarian Army. Upheaval and Imperial crisis gave birth to new nations, but also splintered families and led to extraordinary personal journeys in a transforming Europe. Contributed by Anton Korosec.

However, the result was a remarkable, otherwise unachievable, compendium of personal stories of the war. Some are simple illustrated anecdotes of loss, love, or hardship. Others are significant sidelights on historical events - that we thought we knew well – as eyewitnessed by 'ordinary' people. There is the German seaman's record of the events surrounding the sinking of HMS Audacious, an alternative account of the loss of HMS Hampshire and Lord Kitchener, and a simple postcard sent by the young Adolf Hitler.

It also demonstrated the work still to be done in terms of making searching, translation, and transcription in a multi-language, transnational database easier than it currently is.

Steel helmet worn by a French artilleryman: contributed by Josiane Lefebvre. Just one of many examples of three dimensional items featured in the Europeana 1914-1918 collections.