A history of Europe's relationship with culture

About two years ago, I spent my days in the University of Amsterdam library working on my Masters thesis. I researched the European Union cultural policy which aims to construct a European identity. This blog post provides a brief summary. You can read the whole thesis here.

The Europeana project is almost 5-years-old. But why was it created in the first place? Here's a brief overview about the cultural policy of the European Union which eventually led to the foundation of the largest cultural heritage aggregation project in the world.

When Europeana launched in 2008, Jose Manuel Barroso, president of the European Union, gave the following speech:

'I believe that Europeana has the potential to change the way people see European culture. It will make it easier for our citizens to appreciate their own past, but also to become more aware of their common European identity. And anyone in the world with an interest in literature, art, politics, science, history, architecture, music or cinema will be able to see the important contributions that Europe has made in all these fields, without even leaving their home.'

The idea of using culture in order to construct a European identity was far from new. After the Second World War when six European countries formed the European Coal and Steel Community, which would later become the EU, culture was seen as an important element for the creation of a thriving Europe. Founder Robert Schuman said in 1951:

'Much more than an economic alliance, Europe has to become a cultural union.' Schuman

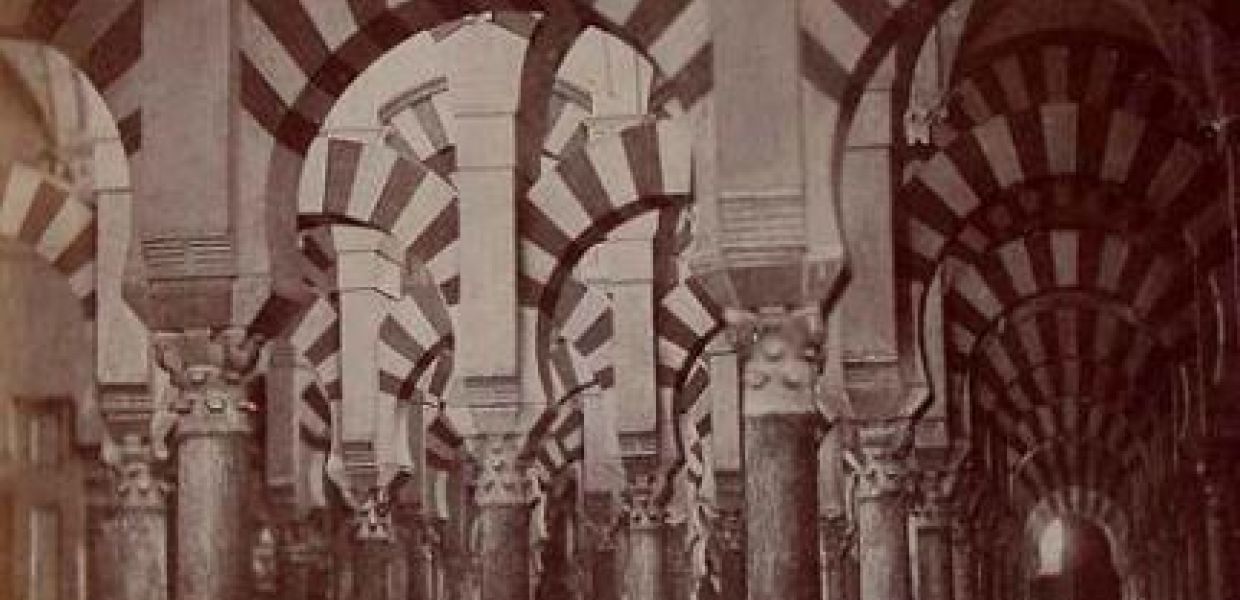

Winner of Europeana's Europe Day competition. Europeana asked the public to nominate items from its cultural collections that expressed the idea of 'Europe'. This image is the interior of Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba, from Fondo Fotográfico de la Universidad de Navarra - Public Domain.

In 1973, the first significant steps towards defining the cultural basis for a European Union were made when the European Economic Community (EEC) signed the ‘Declaration on the European Identity’. This step was the first attempt to create a European awareness.

The declaration led to the introduction of several measures to improve the visibility of Europe in the daily lives of the European citizens. A European flag was created, Beethoven’s ‘Ode to Joy’ was chosen as the European anthem and a standardised European passport created. In 1988, a new policy was introduced which focused specifically on using cultural heritage to demonstrate our common history, involving Europe’s architectural and artistic heritage. The EEC sponsored various arts-related craft and restoration projects and helped preserve a number of monuments that played a big role in the European history, such as the Acropolis, the Parthenon and Mount Athos.

In 1992, the EEC changed into the EU with the signing of the Maastricht treaty. From that point, constructing a European identity became an even more important topic. The European Union had a clear vision of how this European identity could be constructed: with the use of cultural heritage. The idea was that when the citizens of Europe gained a better awareness of their shared identity, they would realise that they themselves had a European identity alongside their national and regional ones. Article 128 from the Maastricht treaty, which specifically concerns culture, states the following:

'The Community shall contribute to the flowering of the cultures of the member states, while respecting their national and regional diversity and at the same time bringing the common cultural heritage to the fore. Action by the Community shall be aimed at encouraging cooperation between member states and, if necessary, supporting and supplementing their action the following areas: improvements of the knowledge and dissemination of the culture and history of the European peoples; conservation and safeguarding of cultural heritage of European significance; non-commercial cultural exchanges; artistic and literary creation, including the audiovisual sector. The Community shall take cultural aspects into account in its action under other provisions of this treaty.' (Commission 1992a: 13)

It is interesting to see how similar the mission statement of Europeana is to the text above. Basically, all you have to do is replace the word ‘Community’ with ‘Europeana’ and you get a pretty accurate idea of Europeana’s core activities. In my thesis I therefore argue that Europeana can be considered Europe’s most visible representation of the cultural policy of the European Union and therefore of major significance.

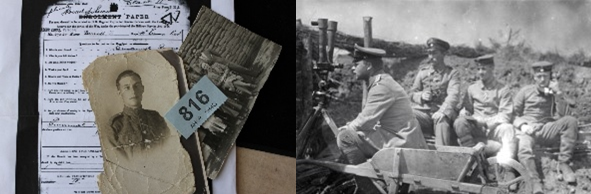

In Europeana 1914-1918, stories from different sides of the First World War sit together. Left, a collection of documents relating to Emmanuel Barnett, of the 14th Battalion Essex Regiment in the UK. Right, Franz Dischinger of 5th Landwehr Division, Germany, with stereoscopic binoculars. Both images are CC-BY-SA.

Instead of policy-makers deciding on what ‘European heritage’ is, the Europeana project allows its users to research European history themselves, create new transnational links between cultures, look at historic events from different national angles, and put history in new contexts. One of the first projects that showed the great potential of bringing together this material from all over the world is the Europeana 1914-1918 project, in which cultural objects from all sides of the conflict are being used to tell a new story about the Great War.