The Yellow Milkmaid Syndrome - paintings with identity problems

If a painting has any relevance, you can probably find a digital copy of it on the internet. In fact, you can probably find multiple copies of it in different sizes, resolutions and colour schemes. A simple Google Image search will show just how many different versions there are on the web of a particular art work. And here comes the problem - it is impossible to know which of the digital versions best represents the original.

To demonstrate just how difficult it it, museum expert and open culture advocate Sarah Stierch has started the Yellow Milkmaid Syndrome blog where she collects and showcases the wide variety of versions of an artwork that can be found online. The results are quite shocking.

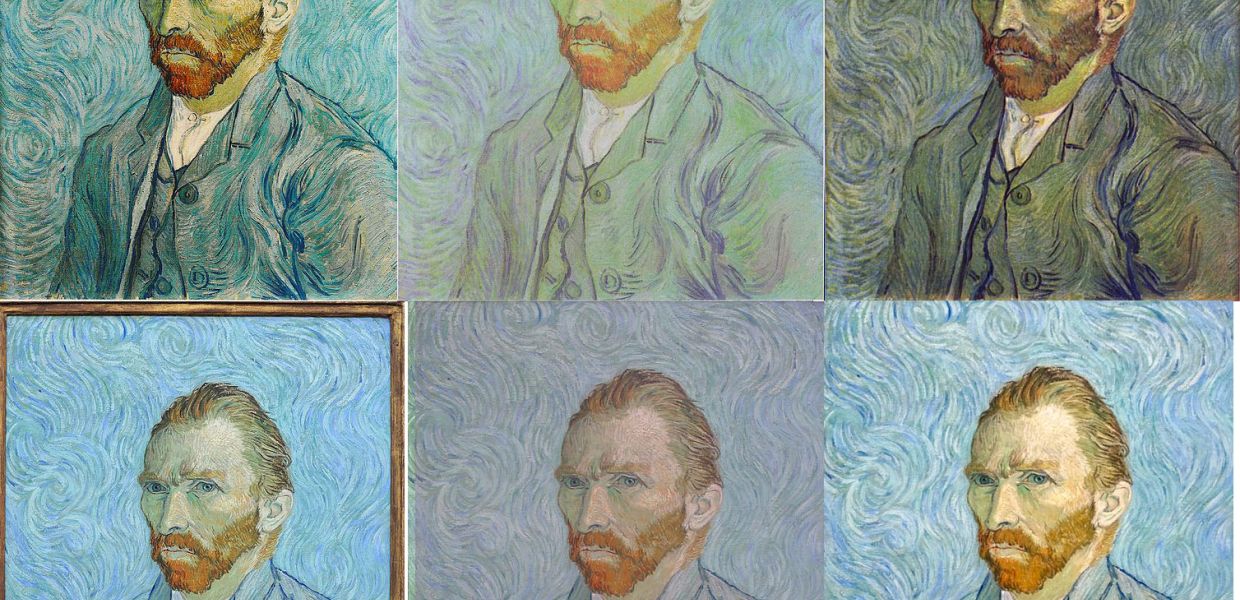

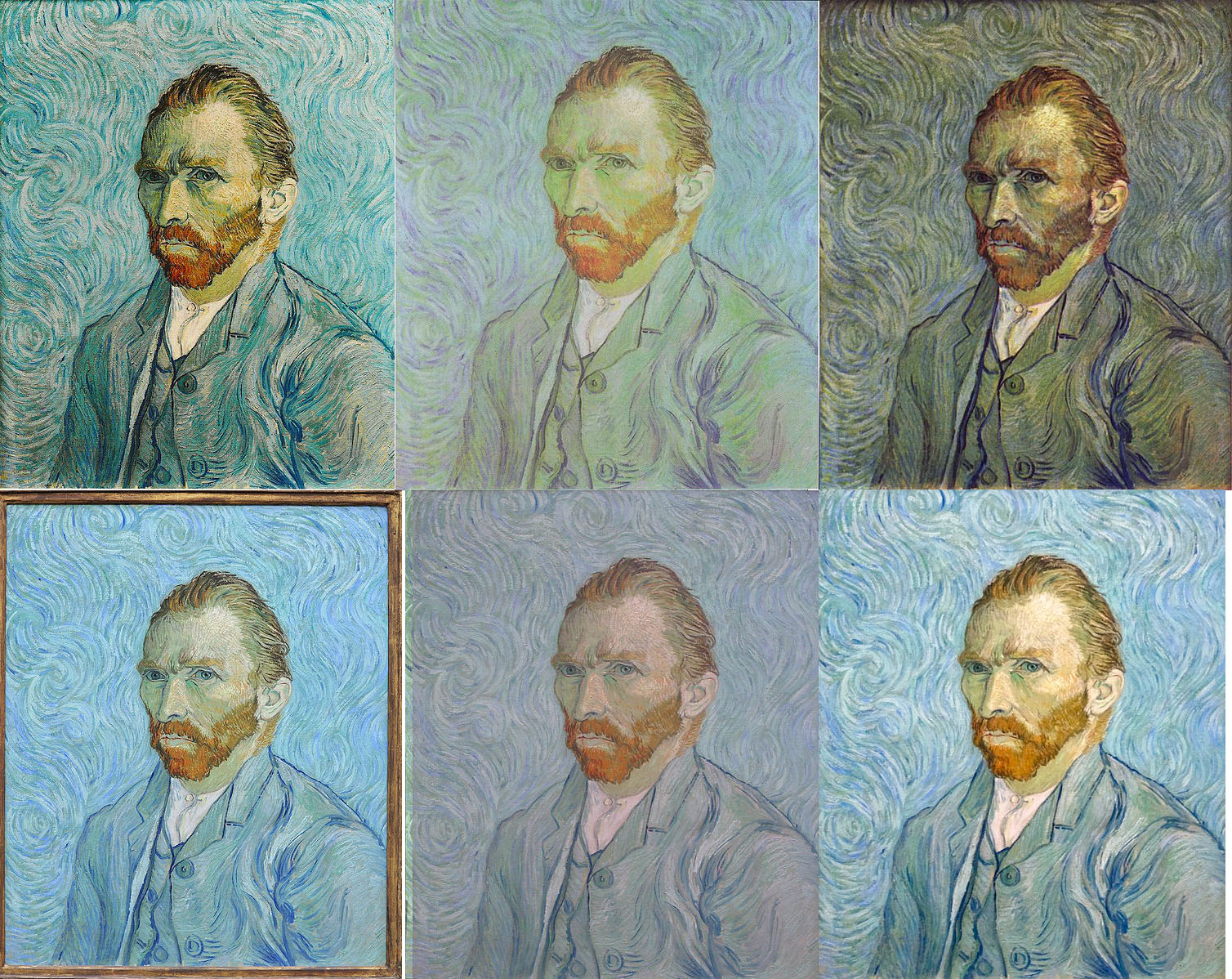

Six different version of Self-portrait by Vincent van Gogh (1889). Located in musée d’Orsay. Public Domain

Six different version of Self-portrait by Vincent van Gogh (1889). Located in musée d’Orsay. Public Domain

So why are there so many different versions of one art work online? Mainly because these were not created and uploaded by the cultural institution holding the artwork, but by users that want to share images online. Often they do not have access to the digitised copy made by the cultural institution, if one even exists, and so they copy it from the Google Art Project, scan it from a book, or find it somewhere else on the internet. Some even take a picture with a cell phone when visiting the museum and edit it afterwards. With no better alternative available, these are the digital representations used to for example illustrate Wikipedia articles, websites about art history, or Pinterest boards - websites with millions of views each day.

The inspiration to start the Yellow Milkmaid Syndrome came from Europeanas’ 2011 Whitepaper: the “Problem of the Yellow Milkmaid”. This discusses exactly the same problem,using Vermeer’s Milkmaid, which is part of the collection of the Rijksmuseum, as an example . Before the museum started to make their own high quality and true colour version of their paintings openly available, all kinds of different digital versions of this painting could be found across the web. It was painful for the museum to see the low quality versions being used everywhere.

After releasing a high quality true to life digital image of the Milkmaid, they found that people quickly started using this version for all kinds of purposes. As a result searching for Vermeer’s Milkmaid now will give you the version from the museum as a first hit. Because the museum itself publishes the digital copies of their objects, it greatly helps the user to find and choose for the authenticated version. A pilot mentioned in the milkmaid paper carried out by the National Archive (UK) for example established that users trusted the National Archive data over similar anonymous data 10 to 1.

The Yellow Milkmaid Syndrome makes quite clear that where a cultural institution does not publish their digital collection, or very low quality reproductions, other versions can probably be found online anyway. In this scenario the institution has absolutely no control what the image looks like, the quality of the images shared, or which versions are being used. Stierch argues that the best way to counter this is not by hiding the collection, but for cultural heritage institutions to take control and publish open access high quality images of their collections.

On a daily basis new entries are being added to the site and everybody is invited to submit examples of their own. Have fun!