The untold story of World War One artefacts: The Geiler Bible

100 years have passed since the end of World War One and we are still unlocking the personal stories and experiences from this period. In the lead up to the Centenary Tour Finale event in Brussels, we offer to shed more light onto one such story and artefact; that of Kurt Geiler and his life-saving bible. We share an in-depth interview with Kurt’s grandson Markus Geiler, exploring the digital transformation of this artefact and the impact of digitising cultural heritage.

The Europeana 1914-1918 project grew from a desire to represent the personal stories from all sides of World War One, using the advantages of digital technologies to preserve, unlock and share cultural heritage items. Launched in 2011 and based on an idea by Oxford University, the Europeana 1914-1918 project held its first collection day in Germany. The then project, now Collection and associated campaign, invited and continues to invite, people to participate by digitising a family item related to World War One to be published online as part of the greater Collection.

Since its launch, nearly 15,000 citizens from 24 countries have digitised and shared approximately 200,000 objects. Further, through digital tools, content and events, the greater campaign it offers people a new way to interact with their culture, their history and each other.

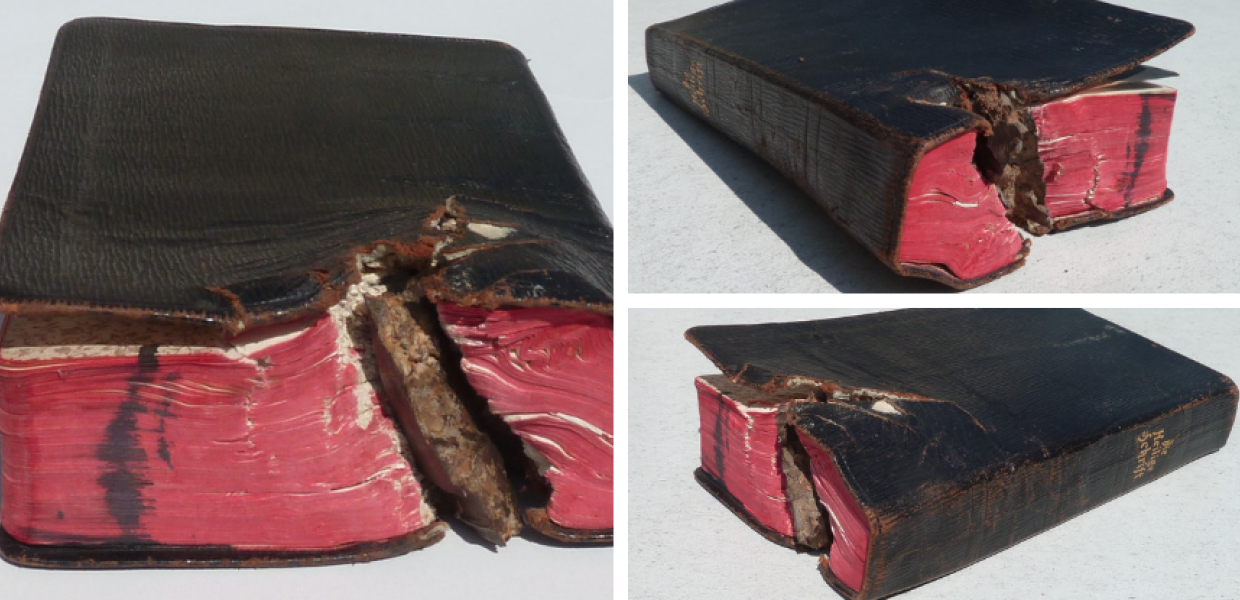

One such item is the shrapnel-pierced bible of German soldier Kurt Geiler. The bible saved a sleeping Kurt, who was resting on it in a trench during warfare in North-East France. When a direct hit on the area sent shrapnel through the bible, it acted as a barrier between itself and Kurt.

According to Markus, the process of sharing in the digital sent a powerful message about the realities of the war, symbolic in the family as ‘a kind of personal anti-war memorial’.

Markus says, ‘I think that exhibits like this one, struck by a shrapnel, very vividly depict the whole futility and cruelty of war. These items should also come out of the family archives and into the museums and online, where they can be made accessible to a wider audience.’

This audience has been expanded even further with the advent of Europeana Transcribathon 1914-1918. Born from the desire to make the shared handwritten letters, diaries and postcards more widely accessible, the initiative relies on volunteers from the public to transcribe these documents and digitise them, making them accessible and translatable online.

So far, more than 23,000 documents have been transcribed by over 1,700 participants across Europe.

Berlin Transcribathon 2017 interviews (music) from Europeana on Vimeo.

For Markus, illustrating the humanity behind World War One, and the human loss acts an important reminder not to repeat past actions.

Markus says, ‘I just believe that history can be repeated. And I believe that mistakes are repeated. After the gift of a long period of peace and the creation of the EU as a peace project, there is suddenly a penchant for nationalism and selfishness. Peace is a fragile entity, so we need to talk about the war, its causes, its upheavals and its atrocities.’

100 years on, it even more important to continue telling these stories and connecting to the real emotion of adverse periods.

In this spirit, the Centenary Tour Finale offers to brings together people and cultural institutions and their contribution to the online Europeana 1914-1918 Collection. The event is held in collaboration with Europeana and the House of European History and supported by the European Commission’s DG Connect. A series of activities offer to showcase the impact of the Collection: from the Transcribathon finale to the presentation of a new World War One game, 11-11: Memories Retold, panel discussions and speeches from European Commissioner for Digital Economy and Society Mariya Gabriel and Member of European Parliament and Chair for the Committee on Culture and Education, Petra Kammerevert.

_________________________________________________

Read the original full interview with Markus below in German.

Was empfinden Sie, wenn Ihr Familienerbstück öffentlich gezeigt wird?

Ich freue mich, dass die Bibel meines Großvaters jetzt für einige Jahre öffentlich zu sehen ist und so viele Menschen an dieser faszinierenden Geschichte seines Überlebens im Ersten Weltkrieg vor Verdun teilhaben können. Ich finde, Exponate wie diese von einem Granatsplitter getroffene Bibel zeigen sehr bildhaft die ganze Sinnlosigkeit und Grausamkeit von Krieg. Deshalb sollten sie auch raus aus den familären Archiven und rein ins Museum, wo sie einem breiteren Publikum zugänglich gemacht werden können.

Können Sie die Person, die die Bibel ursprünglich besaß, etwas ausführlicher beschreiben? Was haben diese Person(en) über den Krieg erzählt / wie wurden sie beeinflusst oder verändert?

Mein Großvater Kurt Geiler wurde 1894 in Waldheim in Sachsen geboren. Er wuchs mit sechs Geschwistern auf, die Familie war sehr arm. Er zog 1913 nach Leipzig, wo er eine Kanzlei- und Sparkassenlaufbahn einschlug und nach Kriegsende und Rückkehr bis zum Oberinspektor aufstieg. 1915 wurde mein Großvater mit 22 Jahren zum Heer eingezogen und kam an die Westfront wo er in den Vogesen, Flandern, Verdun und an der Somme zum Einsatz kam. Er wurde zweimal verwundet, davon einmal schwer. Vor Verdun bewahrte ihn zudem die Bibel, die er als sehr frommer Mensch immer bei sich trug und die er nachts als Kopfkissen nutzte, bei einem Granatvolltreffer in seinem Unterstand vor dem Tod. Seine Kameraden kamen dabei alle um. Nach dem Waffenstillstand am 11. 11. 1918 machte er sich zu Fuß auf den Weg in seine Heimat. Die Bibel mit dem Granatsplitter bewahrte er immer auf und übergab sie vor seinem Tod 1950 meinen Vater, Gottfried Geiler. Mein Großvater, den ich nie kennengelernt habe, sah als frommer Mensch in ihr ein Zeichen einer gnädigen göttlichen Fügung, hat mein Vater mir und meinen beiden Brüdern immer berichtet. Immer wenn es um Krieg, Geschichte oder das Andenken an meinen Großvater ging, wurde uns Kindern die Bibel als eine Art persönliches Anti-Kriegs-Mahnmal gezeigt.

Was ist Ihre Meinung - warum ist es wichtig, dass wir über die Erlebnisse des Ersten Weltkriegs sprechen?

Ich glaube eben doch, dass sich Geschichte wiederholen kann. Und ich glaube, dass Fehler wiederholt werden. Nach dem Geschenk einer langen Friedensphase, und der Schaffung der EU als Friedensprojekt gibt es plötzlich wieder einen Hang zu Nationalismus und Egoismus. Wohin das führen kann, zeigt nicht nur der Erste Weltkrieg. Ich war am 11. November 2014 mit einem deutschen Fernsehteam und der Bibel auf den Soldatenfriedhöfen in Verdun. Ich habe damals gedacht, wie dankbar wir in Europa sein können, dass wir diese Grausamkeiten eines Krieges nicht erleben müssen und dass die Menschen schlauer geworden sind. Ein halbes Jahr später annektierte Russland die Krim und der Krieg in der Ostukraine begann. Frieden ist ein fragiles Gebilde, deswegen müssen wir über den Krieg, seine Ursachen, seine Verwerfungen und seine Grausamkeiten sprechen.