How news once travelled

How was news received and reported in Europe? A question that can only be answered when archives, libraries and museums work together across borders.

A guest blog post by Steven Stegers, Programme Director of the European Association of History Educators (EUROCLIO)

Because of EuropeanaNewspapers and other digitisation projects, millions of historical newspaper pages from across Europe are now freely accessible online. Free access and a standard way of organising information about these sources (such as date of publication, name of the newspaper, text of the article) help to answer the questions of how certain events were reported in Europe when they happened.

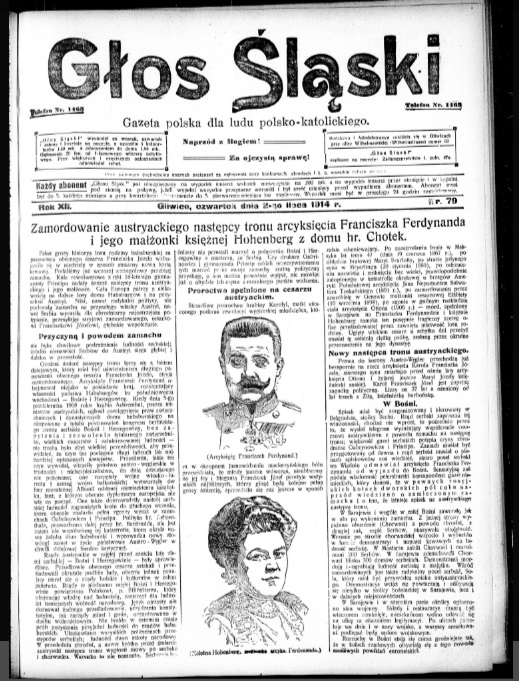

Glos Slaski, frontpage, 02-07-1914, National Library Poland

A blog post by the EuropeanaNewspapers project on how the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and Duchess Sophie was reported in the news in June 1914, illustrates what can be learned from comparing and contrasting newspaper coverage across Europe and how important it is to have knowledge about the source. The blog post was complemented with a broader selection of newspaper coverage that was published as a set on Flickr.

The information about the date of publication helps us to find out how quickly news travelled at that time. In this case it took several days before the news was picked up in other newspapers. The information about the placement of the article (is it front page news, or is it tucked in the back?) and how it is presented (with or without illustrations, with clear headlines?) gives information about the importance given to the event. For example, the issuing of an extra edition about the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and Duchess Sophie by the Illustrirtes Wiener (The Illustrated Viennese) underlines the significance of the event for Austria-Hungary.

The nature of a newspaper article (what is the headline and what is actually reported) helps students to understand how the event was perceived by different groups and individuals. In this case, it is telling what words are used to describe the key people involved (for example, is Gavrilo Princip described as accused, suspect, murderer or terrorist) and the event itself (is it an assassination, murder, killing, death).

Both for the analysis of the importance given to the event and the way the event is covered, it is important for students to know more about the newspapers themselves. In some cases the newspapers contain clues. For example, the text “für Gott, Kaiser und Vaterland!” (for God, Emperor and Country) above the title “Tiroler Volksblatt” (Tiroler People’s Paper) is a clear indication that the newspaper is supportive of the Austrian emperor. When these clues are less obvious it would be very helpful for educators if some background information (such as political orientation) about the newspaper is also accessible.

In hindsight, it is also interesting to know that at the time none of the newspapers were mentioning the danger of the escalation of the conflict into a world war.

The example of the assassination of Franz Ferdinand shows the potential for learning offered by access to multiple archives, museums and libraries. It also shows just how much is required to enable educators to make the best use of these resources. The blog post by EuropeanaNewspapers provides translations of key elements of the sources (such as titles) and gives contextual information about the set of sources as an introduction for researchers. In addition, the pre-selection of sources has already been made and saves anyone who would like to use the sources the time looking for these themselves.

Because this work is both needed and worthwhile, museums, archives and libraries need to work closely with educators to identify what content is most relevant for them to use, and what questions are most relevant to ask and to answer.

Join the conversation on Twitter via #Europeana4Education