Discovery without search: an interview with George Oates

From 11-13 February, the EuropeanaTech conference was held at the National Library of France in Paris. During these two days, Joris Pekel, Europeana’s Community Coordinator for Cultural Heritage, interviewed a number of speakers attending the conference to learn more about their work and their vision for the future of digital cultural heritage.

For the first in this series, he spoke to Seb Chan, Director of Digital & Emerging Technologies at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum and Dan Cohen, executive director of the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA).

Here, he talks to George Oates who recently set up her own company Good, Form & Spectacle. Previously, she worked at the Internet Archive and was the founder of Flickr Commons.

Hi George, thanks for joining us here in Paris.

My pleasure.

How are you and what are you currently up to?

I’m well! I just moved to London a couple of months ago and started a new company. It is called Good, Form & Spectacle and it is a tiny, tiny design studio. I am trying to take a bit of time to work on projects that I really want to work on instead of just leaping into the client zone. We have done a couple of experimental projects already and we’re starting to find some direction. What is important to mention is that I have put a flag in the sand saying I am super keen on cultural heritage and I’d like to bring my knowledge of design and software to the sector.

George Oates at Europeana Tech. By Europeana. (CC BY-SA)

Cool. So I guess most people, or at least I do, know you from the work you have done at Flickr and Flickr Commons. What was your role there, and what will you be doing at your new company?

I started at Flickr before it was Flickr and worked there as the lead designer from 2004-2008. In 2008, I created The Commons program, and had a fabulous year developing the program and nurturing the involvement of about 35 international institutions.

Basically, for the last 10 years, I have worked on trying to design user interfaces for giant globs of content, massive content repositories. Coming here to Paris and EuropeanaTech it feels like there is a lot of focus on moving data around the internet. This is very useful foundational work but I want to focus on how normal humans see content. And that is not only the people out there in the world, but also the staff of an institution. Everybody has to sort of suffer through these terrible search interfaces that are sort of illegible in some ways. When you think about an amazing cultural heritage collection and your first entry point is a search box that is just a tragedy. So I want to explore what kinds of interfaces, that we haven’t even thought of yet, that we can start using when we understand the content we are dealing with. Things like Google are good when you need to search everywhere for anything, but in our world, we know what sort of content we are looking at, so let’s pay a bit of attention to that content and design around it.

Right, so for example, at Europeana we hit 40 million records last month which is a great achievement by our Network. At the same time, this is a massive number and it is very difficult for a normal user to navigate such an amount via a search box. How do you deal with that balance of saying ‘we want to make all of it available’ without running into problems where you overwhelm users.

When I started Flickr Commons in 2008 the advice that I gave to the first participants was to keep their initial offerings really small. We worked with the Library of Congress in the first instance and Helena Zinkham, the chief of prints and photographs, chose two amazing collections to begin with which she knew were appealing to the public. The first upload was something like 500 images, which is easily consumable. You could literally sit down for an hour and look at all of them, which I think is great. More recently with the releases of the British Library and the Internet Archive, which made a splash of one million images each, that content is now dominating the view. If you do a search on Commons now, you see all of these illustrations and stuff from books. As much as I love that the content is being shared it also generates this issue that you mention.

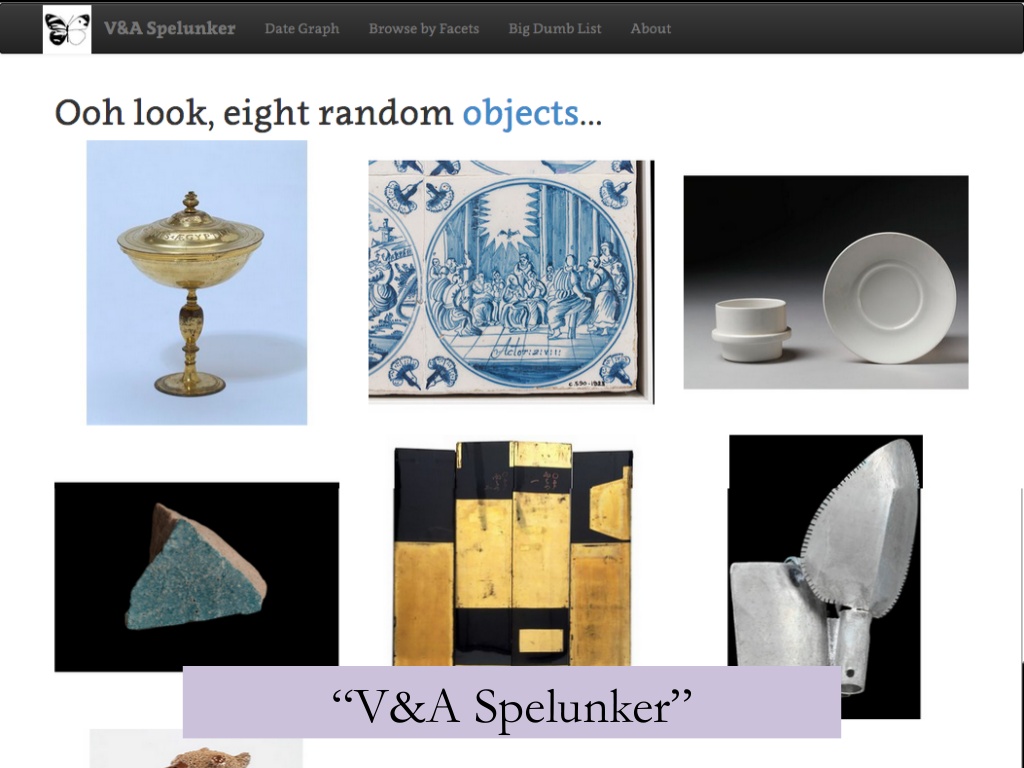

A slide from George Oates' Closing Plenary at EuropeanaTech 2015 showing V&A Spelunker. By George Oates.

So you have to come up with new ways to surface certain bits of content depending on who your user is, I guess?

Well, I think it is dependent on the content. There is an opportunity to return to thinking about your own collection and how to see it online, in a different way to a list of ordered search results. We are getting fairly good at passing data around by now. You have accumulated 40 million records in how many years?

Five years, but the majority in the last two.

Right, that is great, but I would love to see the information and tech folks pause for a moment and try to make their information better and more accurate, and just think about it a bit. Look at the content again and think about how people are actually using it. Can you see that? And how do you see that? Meanwhile these giant aggregators are still being used and are useful for all kinds of things, but maybe it is time to come back to your own content again and really start helping people find stuff that they like. It’s done so, so well in the physical realm, but we’re not there yet online.

I guess it comes back to the discussion I have had a lot this week. And that is the balance between the question of whether you publish whatever you can publish and let other people come up with ways of how to make the most out of that, or, do you publish more curated batches that suit your user needs? And, if so, who decides who your users are and what they need?

Yes, right. So for example I have heard a few people talking about their projects saying that the thing that they are making is either for some researchers, or the general public. These are not user groups. That is a clear message to me that these people have no idea who uses their stuff. You have got to cross that bridge. You got to say ok, maybe I should actually talk to some of my researchers that use my content and sit with them as they use my search tool. Listen to them. Maybe internally we could also start working on figuring out ways to draw pictures of our catalogue that help us inform ourselves about it. I love it when, in a physical collection for example, an archivist makes a discovery in her own collection because she doesn’t know what’s in there. I wonder if we can sort of replicate that kind of feeling with software tools internally, so that people understand what content they actually have, and then can frame it better - and not rely on search so much.

I think this is very much in line with the direction Europeana is currently heading. By offering the data via the API, you can pull out the data that you want for your use case. But in order for a user or programmer to do this the data needs to be of a certain quality. Simply copying your internal database to the web is not going to do the trick. What kind of steps do you think an institution should make in order to do this in the right way?

I don’t know how to say this politely, but it is pretty rare that a cultural institution is on the cutting edge of tech things. The work that Seb Chan and his team have managed to do at the Cooper Hewitt is one of the first instances in the world where I think they have done it right. They have actually created an institution that has got digital feet on the ground.

A lot of this work is about precedent. It is about finding somebody who is doing great work and emulating them. For me it all comes back to use, like we were talking about before. If you don’t know how your stuff is being used, or who is using it, or when it is used, you will remain in a black hole. Even if you put your stuff online. That is maybe where the front-end element and understanding the use of things can be handy. You could simply try to apply some of the techniques that designers use in order to understand the crowd that they are working with. So talking to people, finding out stuff, and of course measuring things.

So yes, precedent, and attempting to learn about design might be useful, but I am saying that because I am a designer! Engineers on the web today have huge communities of practice and Europeana is obviously trying to foster that so it is up to you, in your position, to speak about best practices, and share tools that you think are good. And again, it is not just about sharing all the tools, but rather pointing out that this particular one is the one I should use for my purpose. Also overviews like that need to be designed and edited. You need to give direction rather than just present a giant buffet.

George Oates with Seb Chan at Europeana Tech. By Europeana. (CC BY-SA)

Do you think that institutions are becoming more open to this kind of direction? Because it is quite a mind-shift to make to be comfortable with the fact that you no longer control everything in your collection or how it will be used.

Yes, absolutely. And certainly the rest of the world is far more open, though perhaps interestingly, some big companies like Netflix are actually closing down their public APIs apparently due to resourcing issues. I think it is important to keep reminding the institutions that they own the canonical copy while their records and content are in the wild. It’s not a read/write situation. It is not that you are opening up your actual vaults. You can treat it very lightly and experiment. Make an export of a selection of your database, which you know is interesting and has no copyright restrictions, and shove it on the internet. After that it is a matter of shouting really loud that that material is available to people, perhaps have an event at the institution, and see what happens.

I think a lot of these fears can be treated in the way we treat normal human fears. You keep supporting and encouraging what they are doing. And I think that there is a lot you can do in your role as Europeana by saying ‘that is really awesome’ and sharing their efforts with the rest of the world.

Great. So you have attended EuropeanaTech... What is the main thing you will take home with you?

I was really excited to find out that the thoughts of some people outside of my field like researchers very much resonate with what I am currently thinking about. For example Aki [Akihiko Takano, National Institute of Informatics in Japan], who is working on associative search. I like the tone that is being set: a search box is not the best way to navigate this kind of content. And I am going to expand on that during my talk this afternoon. Search boxes are illegible. It doesn’t present you with any scale or direction of any kind. And that is what cultural heritage institutions are so good at. What they are best at is making people realise which painting or book or whatever they should look at. I am excited to hear that there is serious doubt in the power of search, or at least, its appropriateness as our default interface into cultural collections.

Excellent. With that I would like conclude. Thanks for taking the time to talk to me and keep up the good work.

Thanks, you too.