Details make the design: an interview with Chris Wild

On 9-10 July, Europeana Creative's Culture Jam was held at the Austrian National Library. During the two days, we spoke to some of the speakers attending the conference to learn more about their work and their vision for the future of digital cultural heritage. Here, Milena Popova, Business Development Manager, speaks to Chris Wild, creator of Retronaut, and author of Retronaut: The Photographic Time Machine published by National Geographic.

What do you think are the biggest challenges in connecting heritage to the creative industries?

I think of two challenges. One is that the term “the creative industries” is very broad and we use it to encompass anything that includes some degree of creativity and that can range from dance to record labels and everything in between. So, if we are a cultural heritage institution and we have materials or assets which we think are of value for these industries, then we need to start by saying for which industries and in what way.

So we need more segmentation, more specifics?

Yes… Retronaut is kind of a start-up and one of the things I’ve learned about start-ups is that it is very easy to answer the question “Who will use your product?” with “Everyone” i.e. everyone will use our product, will use our website.

This may be true and it certainly makes everything sound very exciting and simple but it usually means that we end up with a product that nobody actually loves and, especially, nobody wants to use. One of the great questions for a new start-up product is not “Who will use it?” but “Who would be highly disappointed if our product no longer existed?” As cultural institutions, we should look for people who will miss our “product”, our cultural heritage assets, people who will be significantly disappointed if they didn’t get to see or read or interact with our product.

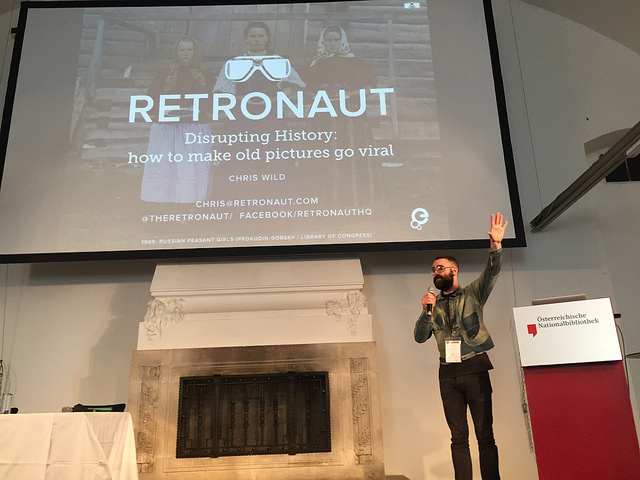

Chris Wild presenting at #CultJam15. Image: Europeana Creative CC BY-SA

But what about the case when people just don’t know about the existence of this product? They can’t be disappointed about something they don’t know about.

That’s why we need to start not with what we’ve got but with what people actually want. Because if we don’t do that, we are acting as though our collection is of more significance than our audience.

When we take that view, we believe people should want to engage with our resources. However, if we reverse that perspective and start by asking what is it that people actually want that may connect to what we have to offer, then we can start to tailor what we show.

Let’s say we have a million digitised objects which the world has not seen. We could argue that if only the world could see our objects, it would engage with them. The implication of that approach is that we need to show the world all the objects until one accidentally triggers the audience into engaging. Whereas if we start with the question “what is it people actually want to see or do already?” and select objects that fulfil those needs, then we have much faster and more efficient engagement between our objects and the audience.

So, in summary, the first challenge is not to think of the creative industries as a whole but as specific sectors, companies and individuals, and question in detail what those groups are seeking.

The second challenge relates to how we connect the creative industries to cultural heritage. Most probably, the creative industries don’t frame the question this way. They don’t walk around wondering how they can connect to cultural heritage; they are walking around thinking about whatever creative challenge they are working on or doing. So, our challenge is how we find out what, in our collections, might be important to what the creative industries are already doing.

What are you most excited about in that area right now?

Two main points. It is not that I am excited about budget cuts in the cultural heritage sector; neither that there isn’t enough money for cultural heritage; however, in my own experience, the best opportunities, the most important, life changing moments have come when things collapse.

Very often this is related to economics. Let’s give you a personal example: when Retronaut all but ran out of money because I wasn’t thinking in the right way, or because I wasn’t able to raise the investment I wanted - that forced me to think very precisely about not only what I was doing but also who I am. And it is through figuring out who I am and who I want to be in a very specific way that now I am in a very different place, in a very positive place. Nobody likes to be in a situation when money is scarce; however, I know personally that from this come the best opportunities.

Chris Wild presenting at #CultJam15. Image: Europeana Creative CC BY-SA

The second one is that I am devoted to the Rijksmuseum. The Rijksmuseum is, in the words of Simon Sharma, “a curatorial revolution” and I agree with this [statement]. All the things I’ve looked for in a museum are there, to the extent that I, slightly radically, now say that it is only possible to either be like or be unlike the Rijksmuseum - there isn’t another paradigm.

What are you most excited about the Europeana Creative project?

Clearly, Europeana Creative has been about trying out what’s possible to do with cultural heritage and all of these experiments have worked out as all of them are about learning. The other thing that excites me is the quality of some of the experiments. All of the experiments are good but some of them are especially good. One of my favourites is VanGoYourself. Everything about that is right to me – its focus is very small and specific, and its branding & presentation are beautifully executed. I agree with designer Charles Eames who said ‘the details are not the details. They make the design.’ In VanGoYourself, all the details are right, which is both rare and special.

What do you hope to see in the next few years that shows a meaningful connection between creative industries and heritage?

The core thing I’d like to see happening (and, again, I see it already happening in some places like the Rijksmuseum), is that GLAMs, particularly museums, are aware of what they have that no other place has.

This is often a spectacular building but, more importantly, unique and special objects. I want the museum to be a physical place and I want to have three-dimensional objects. So, if the focus shifts back on to museums as physical places with physical objects, it will become really clear what their value to almost any of the creative industries. Once you have segmented the creative industries, you can see really easy connections between each of them and an amazing physical place and – especially – the objects inside. So, tightening the focus on that will make the value offering of museums and other institutions to creative industries much easier to articulate. As a result, we will see many more collaborations with the creative practitioners who want to express what they are doing in a special place or with a special object, and with particular audience, all three combined. That’s what I’d like to see happening.

And digitally, I would love to see, and I do see this, especially in Europeana Labs, a shift from a focus on quantity to quality. As an example, I would like to see more online projects that show big and beautiful images, and only big and beautiful images. I would also like to see less focus on metadata, and more focus on data - and by data, I mean images.

Images are so often used as illustrations for textural information, rather than as information in their own right. So, digital projects that are both smaller and better - smaller scope, better result.